Originally posted on the WeChat public account "Look at the Winter Solstice", the editor [very looking forward to] feedback and discussion

I like the kind of film that allows every audience to interpret it freely, as if this film is their own work.

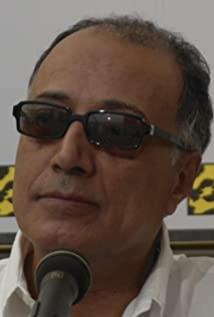

---Abbas Kiarostami

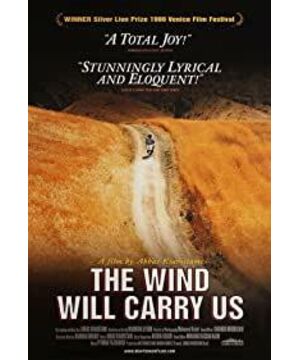

Before discussing the content of "Gone with the Wind" (1999), I would like to briefly mention the general environment of Iranian films and the film director Abbas. Before 1979, Iran was pro-American. Film investors are mostly from the United States, and the style of the film is also biased towards American Hollywood. Action movies and musicals are popular in theaters. The Islamic Revolution in 1979, and the Iranian film industry suffered heavy losses in the following four years. This has both economic and political reasons.

In 1983, the Iranian government realized that film can be used as an incompatible tool with the United States, so it invested in the establishment of the Farabi Cinema Foundation, dedicated to boycotting Western "vulgar" films and developing Iranian art films. [1] This move has guided the development of Iranian films in the direction of artistic films, and indirectly has made Iranian films nominated and awarded many times in major international film festivals. Although the government has relaxed the censorship standards, there are still many restrictions. For example, scenes of sex and violence are not allowed in Iranian movies, and unmarried heroes and heroines cannot even hold hands. Therefore, many Iranian directors choose to use children as the protagonists to mirror the stories and lives of adults. [2]

Most of Abbas's works were created in such a post-revolutionary period. The classics include his "Country Trilogy"-"Where is My Friend's Home" (1987), "Life and Growth" (1992), "Lover under the Olive Tree" (1994). There is also Abbas's favorite work "Close-up" (1990), which won "The Taste of Cherry" by Palme d'Or in Cannes in 1997 and "Gone with the Wind" that I want to talk about this time.

In "Gone with the Wind", an engineer from Tehran takes his team to the remote village of Syakh Daleh in Iran. The film tells the story of the communication and interaction between the engineer, the little guide boy and the local people in the village. The film never clearly explained the purpose of their party here. It is reasonable to guess that they want to record local funeral customs, so they waited for the death of a dying old woman in the village. The delay in the death of the old woman made them impatient and passive, who had been doing nothing in the village all day. The old woman passed away on the last day, but the engineer drove away only after taking pictures of the funeral crowd.

Similar to the mainstream development trajectory of movies in the third world countries, the works of Abbas and most Iranian directors are biased towards the realistic style of realism. In "Gone with the Wind", you can see a lot of Italian neo-realist technology and the influence of the thoughts at that time.

In practice, like the pioneering work of Italian neorealism, "Rome, the Undefended City" (1945), Abbas's "Gone with the Wind" was useless with a script. He took a two-page outline to the village of Siah Daleh and was ready to shoot. This kind of scriptless approach is a test of the cooperation of all the crew, but it can minimize the influence of artificial presuppositions in the work, and make the story closer to the real life of the local area.

In addition to no scripts and on-site shooting, Abbas also used a lot of long lenses and fixed lenses to allow characters to travel freely in the frame. This approach preserves the integrity of time and space well, and is therefore closer to reality. The most typical example is the section where the little boy pointed out the old woman’s residence for the engineer: in the one-minute long shot followed by the camera, we watched the protagonists walking through the village, walking down the stairs, being covered by the roof, and Walk out, be blocked by a wall, and go up the stairs... Suddenly, the architectural/spatial characteristics of this village are captured: crowded, uneven, like a maze.

In terms of content, Abbas has left the audience a lot of room for self-explanation and supplementation. These are the same as the views of the Italian neo-realism and contemporary realism theorist André Bazin:

Many incidents just happened, as if there was no obvious motivation. At first glance, they can only be explained by "it just happened", but the director cut them together or made it happen again. For example, the events in the entire movie are not very logical: occasionally when there is a call, the engineer went to the top of the mountain to answer the phone; met a well digger on the top of the mountain and chatted with him; came back and washed his face and asked the little boy about the old woman. Circumstances; spoke to the landlord; another phone call... even the whole film did not clearly and directly tell the audience what the purpose of the engineer was here.

Another example is when the engineer behind answered the phone and saw a crawling tortoise. He turned it over with his feet and drove away. And the next time he came to the top of the mountain to answer the phone, he saw a beetle rolling a dirt ball. Why arrange close-ups of these two animals? You can say that the first time the engineer was retaliating against an old life because the old woman did not die; the second time he saw the power of life in the chafer after receiving the call, or the absurdity of his own life. There must be other explanations, and we can never be sure what the person on the other end of the phone said to the engineer. In this way, "Gone with the Wind" left many ambiguities. Just as it is impossible for us to grasp everything and clarify all causal logic in reality, there are always places in movies that require speculation and association from the audience. In the film, the director’s authority is rarely revealed, and the task of finding the key points and the burden of interpretation fall on the audience. In summary, the audience came to watch this movie not to be taken with a designated dream, but to enter and live in another reality.

If you analyze "Gone with the Wind" only from the perspective of realistic expressions, it feels like a baby is buried. After all, these techniques and concepts have been discussed and applied by Italian Neorealism, American Post-War Hollywood, Indian Parallel Film Movement, and Brazilian New Wave. "Gone with the Wind" surprised me because of Abbas's thinking about the "real".

One characteristic of Iranian films is that their films are very reflexivity. Reflexivity refers to the fact that there are elements in the film that emphasize the film itself or remind the audience that what they see and hear is artificial. For example, at the end of "The Taste of Cherry", what we are waiting for is not the suicide ending of the protagonist Badii but a documentary of the filming process. The actor playing Badii walked to Abbas and handed him a cigarette. The soldiers were resting and the sound engineer was working. This ending seems to tell the audience, "What you saw for an hour and a half was fictional. I will tell you how we fictional it." Another example is "Who Can Take Me Back" by another Iranian director, Jaffa Panahi. Home" (1997). The little actors made an emotional strike, so the movie turned into a tracking documentary. The crew came into the scene, and the film began to film the little actor's own experience of going home and her "real character" outside the play. But isn't the second half of it designed? In short, some Iranian films like to use images to walk the border between reality and fiction. Sometimes the audience can't distinguish what is true and what is false, as if the two cannot be easily distinguished.

In "Gone with the Wind", Abbas's thinking about reality is embodied in two levels: reflections on the characteristics of film recording reality and reflections on himself (the works of realist directors).

Bazin believes that film should be used to record reality, because the biggest difference between it and other art forms is that it can record reality completely objectively. The most basic structure of a movie is a photo, and a photo is a trace of reality left on the film through physical exposure, and has not been artificially processed. Bazin admits that film is not reality, but thinks it is an afterimage of reality, an "asymptote of reality" (asymptote of reality). [3] In "Gone with the Wind", Abbas reflected on why movies can only be an asymptote to reality from a practical perspective.

In the first part of the film, there is an engineer drinking tea in a teahouse in the village, watching a dispute between the proprietress of the teahouse and a male tea customer over "whether women are working". The engineer found it interesting, so he picked up the camera and wanted to take a photo. As a result, the proprietress told the engineer "not to take pictures" very politely, and then continued to argue with the tea customer. The end of the movie also involved taking pictures: the old woman eventually passed away, and the engineer saw the women in the car, wrapped in black veils, in long lines to see off. He moved his fingers quickly to take the picture, and the women looked at him and whispered to each other.

Most of the movies we have seen are trying to hide the camera. The audience watched the movie and the actors acted them as if they would do it in their lives, as if they were unaware of the audience/camera gaze. But in "Gone with the Wind", Abbas puts the influence of the camera before the audience: the existence of the camera makes the subject realize that they are grasped, they know that they are being stared at, and their actions will be recorded. Therefore, either directly refuse to be recorded, or change one's original behavior to a certain extent. Just like a psychologist observing a child's behavior from a distance, if the psychologist has stood by the child and made him aware that he is being observed, the observed data is of little use. Because the existence of a camera will change reality to a certain extent, it is said that film can only be an asymptote of reality.

In addition to the fact that the film can only be "gradually" true in practice, Abbas also discussed the limitations of film content and the existence of time and space outside of the lens in "Gone with the Wind".

When watching "Gone with the Wind", you may feel a strong sense of discomfort. This discomfort comes from seeing and hearing-you have not seen what you think you should see for a long time (or even forever), you hear it but you just can't see it. For example: engineers often greet people off-screen or have long conversations with them; the audience has never seen the faces of other people in the engineering team; we have never seen the person who sinks the well. Their voices came, but we just "invisible".

This "invisible" reminds us that there is more outside the lens of the movie, and reminds us that the relationship between the movie and the surroundings is continuous (this is the biggest difference from drama). The "invisible" in the movie not only gives us a sense of reality, but also emphasizes the limitations of the movie we see before our eyes (only part of it can be seen).

Having said that, you may ask, why does the director have to reflect so much on the medium of film? Or why would your friends keep saying "There is reflexivity here" or "Reflexivity is seen there"? My current thinking is that when we discuss exploring the reflexivity of movies, we are exploring, understanding, and constantly approaching the true essence of the film as a medium, just like Bazin is constantly exploring what movies are. Its motivation may be a simple search, or it may come from a desire to survive-we try to understand its limits, its irreplaceability, and its uniqueness. We hope it will continue to live and move forward.

Finally, the center of "Gone with the Wind" is also the director's thinking about making a movie. To put it bluntly, Abbas is asking himself "what am I doing?" The 1997 "Taste of Cherry" award made Abbas famous internationally, and his work has also been sought after by Western critics. But some people say that his works cater to the expectations and specific tastes of the West for third world countries (such as Iran). He is not shooting real Iran but something expected.

This type of criticism is not uncommon, especially when third world directors make films with local customs (such as "Song of the Earth" by Indian director Satyajit Rey). In the face of such subjective criticism, it is difficult to give an answer: the director’s work does not necessarily evade what the critics expect; the content of the work showing national characteristics is inevitably one-sided. As a result, a single work has received international acclaim, allowing the audience to have a specific impression of a certain region, and at the same time, because of the inevitable one-sidedness of the film, they have to face the question of "This is not the real place (Iran)". But I think Abbas is very powerful in thinking and rebutting this criticism: he is looking for commonalities. And this is exactly what the movie should do.

The medium for finding commonalities is the role of the engineer. As Abbott analyzed, the engineer was curious about this ritual at the beginning, and had a personal presupposition--he looked forward to seeing class exploitation and individual survival pressure in the village different from those in the city. But in a conversation with a local young student, he realized that this kind of survival pressure and self-interested tendency also exist in closed villages. [4] The young man and the engineer talked about the two scars on his mother's face: one was drawn by his mother to express her heartfelt and sadness to his father when his aunt died; the other was his father's boss When her mother died, in order to help her father keep her job, her mother drew a line on her face to express the heartache that the family felt empathetic and sincere to the boss. How absurd, but that's it.

At the end of the film, although the old man passed away, the engineer took a few photos and drove away. The choice of the engineer is also the answer given by the director in the face of doubt. Because the content of the film is the thinking of the director, and the role of the engineer is also equivalent to the director Abbas himself, because they have similar authority. Just as the off-screen director controls the movie, the on-screen engineer uses a camera to record (grasp) other characters in the movie, and has the highest authority within the movie. Abbas even made the engineer's authority high enough to grasp the audience by gazing. In the scene where the engineer shaves, the engineer looks at himself in the mirror, but the mirror is replaced with a camera, so what the audience sees is that the engineer is carefully "studying" the audience and speaking to the audience. The roles of watching and being watched have been switched, and the audience seems to have been placed on the bright side from a dark box.

After realizing the commonalities between the city and the country (international and Iran), the country (Iran) is no longer a static "object" and fantasy object. Many human things have the same social characteristics. At the end of the film, the engineer gave up the presupposition, walked down from the position of authority, and threw away the leg bones that had been in the car by the river. The leg bones picked up from the cemetery in this village symbolizes the illusion of ancient rituals, and it drifts away along the water. The wind will carry us. The wind will carry us.

[1] Cook, David A.. A History of Narrative Film . New York, WW Norton& Company, 2004.

[2] "Cinema Asia: Iran." Films On Demand, Films Media Group, 2007, fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=16244&xtid=40155. Accessed 3 Aug. 2020.

[3] Andrew, Dudley. Major Film Theories . Oxford University Press, 1976.

[4] "The Wind Will Carry Us: Cinematic Scepticism." Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy, by Mathew Abbott, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2017, pp. 32–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366 /j.ctt1g052r5.5. Accessed 4 Aug. 2020.

View more about The Wind Will Carry Us reviews