clit2088 final The midterm I just handed over to my mother has to be written again and the final has to be written again from another angle. Who let me choose it myself?

There is a little mention of post-structuralism and how to really get rid of Freud-Lacan-led psychoanalytic theory and symbolic order and law of father for feminists. There is also mention of julia kristeva maternal semiotics... a lot anyway

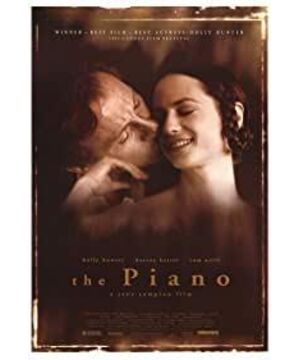

Can a Post-Structural Feminist Truly Escape from the Symbolic Order?: The Piano Revisited

Winning the 1993 Palme d’Or and three Oscars in the subsequent year, Jane Campion’s The Piano had not only gained the mainstream’s recognition but also obtained much feminism-positive reception among critics. Many female spectators find themselves greatly affected and empowered by the film, both in the emotional and sensual dimensions (Klinger 19). Stephen Crofts considers it “one of the supreme signposts of the art of feminine sensibility” along the development of feminist film (143). Despite its self-conscious effort to enunciate the repressed femininity under the phallic power, other evidence from the film, however, highly alludes its inevitable association with Lacan’s symbolic order. This essay argues that The Pianois a failed attempt at breaking free from the symbolic order and therefore cannot fulfill its post-structural intention to valorize female empowerment under the phallogocentric hegemony. In the concluding paragraphs, I shall push this argument a step further by identifying what makes a feminist film truly self-sustaining and emancipated from the psychoanalytic structure, in relation to Anu Koivunen’s scholarship.

While a considerable amount of mainstream as well as art house films extensively exercise the exhibition of female spectacles and portrayals of female’s submission to the traditional patriarchy, this conception of conforming to a presumed social order is widely interrogated under the post-structural ideology. Post-structural feminists such as Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray have in their works disapproved of the assumption of Oedipal heterosexuality in Freudian psychoanalysis studies and suggested the possibility of femininity empowerment through emphasis on the essentialism and inherent semiotics. Laura Mulvey calls attention to exploring a radical position in narrative cinema that deconstructs the pervasive male gazing pleasure and represents femininity beyond the scopophilia dimension. Nevertheless,she recognizes the underlying complication of such exploration, with the challenge being precisely “how to fight the unconscious structured like a language… while still caught within the language of the patriarchy” (2182).

In light of the difficulties that challenge the de-objectification of the male gaze, The Pianoto some extent does play its part in advocating the kind of feminist cinema ideal in Mulvey’s account that reflects upon and hinders the male gaze. In his 2003 essay titled “Jane Campion’s The Piano: The Female Gaze, the Speculum and the Chora within the H(y)st(e)rical Film”, Jaime Bihlmeyer identifies several cinematographic and narrative means adopted by the film that strive to frustrate the male gaze by initiating a female gaze perspective and constantly mocking the cockiness of the phallocentric construct. He posits that Ada’s silence, that is, her repression of the linguistic ability, signifies a passive aggressive defiance of the symbolic order in which language plays a dominant role, and that by emphasizing this silent nature in coherence with Kristeva’s notion of pre-lingual maternal semiotics, the film manifests the enunciation of femininity. Here, I am fully aware of Bihlmeyer’s prime intention to locate Ada’s characterization somewhere in opposition to the pre-existing symbolic structure,yet I argue that a text can never be seen truly protesting against the social patriarchy without being excluded from the symbolic realm. In other words, one should find a way to acknowledge the pervasiveness of the symbolic order as well as its constraints and self-sufficiency, meanwhile consciously position oneself outside the frame – despite the complication of the struggle in Mulvey’s account – and seek for other orders and inclinations. Therefore, the character’s silence as in Bihlmeyer’s analysis cannot prove adequate to challenging the symbolic order because it is “still caught within” the discourse of linguistic significance and more importantly, within the prevailing order.one should find a way to acknowledge the pervasiveness of the symbolic order as well as its constraints and self-sufficiency, meanwhile consciously position oneself outside the frame – despite the complication of the struggle in Mulvey’s account – and seek for other orders and inclinations. Therefore, the character’s silence as in Bihlmeyer’s analysis cannot prove adequate to challenging the symbolic order because it is “still caught within” the discourse of linguistic significance and more importantly, within the prevailing order.one should find a way to acknowledge the pervasiveness of the symbolic order as well as its constraints and self-sufficiency, meanwhile consciously position oneself outside the frame – despite the complication of the struggle in Mulvey’s account – and seek for other orders and inclinations. Therefore, the character’s silence as in Bihlmeyer’s analysis cannot prove adequate to challenging the symbolic order because it is “still caught within” the discourse of linguistic significance and more importantly, within the prevailing order.the character’s silence as in Bihlmeyer’s analysis cannot prove adequate to challenging the symbolic order because it is “still caught within” the discourse of linguistic significance and more importantly, within the prevailing order.the character’s silence as in Bihlmeyer’s analysis cannot prove adequate to challenging the symbolic order because it is “still caught within” the discourse of linguistic significance and more importantly, within the prevailing order.

Moreover, not only does this silence fail to fulfill the passive aggression toward the patriarchal order, the character’s bodily image is also enlarged precisely due to the absence of linguistic expression. The spectator only hears Ada’s speaking voice twice, in the beginning and ending scenes respectively, in the form of voiceover narration instead of a progressive narrative instrument that takes place simultaneously with the visual narratives. As a consequence, the spectator autonomously concentrates their attention – of which the total amount is usually split between two perceiving senses – on the visuals solely. It is undeniable that the film exploits this feature by providing the audience with the option to see more of her body. There are various shots that elaborately display the muted character’s different body parts,of which the most notable are the ones in the scenes of the first few piano lessons purposefully showing her pale neck, thin fingers and arms, bony and stubborn back, and reluctant facial expressions. All these body features, although not necessarily overtly provocative, are presented in a particular way that triggers the sensual fascination. The carefully opted body parts to be shown exhibit functions equivalent to directly addressing female specificity to the extent that they perform like an erotica alternative that primarily affects the active heterosexual males both in front of and behind the screen. Notwithstanding that in certain parts of the film, the classical male gaze is deliberately unfulfilled through unusual arrangement of shots indicated by Bihlmeyer’s essay,the film as a matter of fact obliquely encourages the engagement of the male gaze by replacing the linguistic expressiveness with alternative spectacles. In this sense, it is contradictory to assert the post-structural intention ofThe Pianoas it ultimately falls back into the symbolic order being a fundamental consumer of the phallogocentric economy.

Another feature that I also consider a signature of pseudo-enunciation is the displacement of the phallus. There are three scenes that involve the presentation of Baines’ full nudity, among which two are associated with certain degree of sexual activity; the bits of presence of the phallus in each scene are carefully crafted with the precise use of staging and lighting so that the spectator never encounters an explicit display of a penis yet cannot resist the subtle tease offered at hand. Some may propose that the intention behind the missing phallus is to empower the femininity within the symbolic order by suggesting the possibility of incorporating a female gaze perspective, provided that the consumers are primarily but not limited to heterosexual females. However,so insufficient is this playful withdrawal of the phallic presence that it only draws more attention to the phallic power, to male’s superiority in the symbolic patriarchy due to phallus possession, and correspondingly to the repressed femininity due to the conscious lack. The seemingly absent phallus does not neglect the overall outcome of the phallic power; on the contrary, the phallic attributes are intensified by the film’s happy ending of Ada reuniting with her one true love, an ending reminiscent of the overused marriage closure in the Western narrative system. As Mulvey identifies in her “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’sand correspondingly to the repressed femininity due to the conscious lack. The seemingly absent phallus does not neglect the overall outcome of the phallic power; on the contrary, the phallic attributes are intensified by the film’s happy ending of Ada reuniting with her one true love, an ending reminiscent of the overused marriage closure in the Western narrative system. As Mulvey identifies in her “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’sand correspondingly to the repressed femininity due to the conscious lack. The seemingly absent phallus does not neglect the overall outcome of the phallic power; on the contrary, the phallic attributes are intensified by the film’s happy ending of Ada reuniting with her one true love, an ending reminiscent of the overused marriage closure in the Western narrative system. As Mulvey identifies in her “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’sAs Mulvey identifies in her “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’sAs Mulvey identifies in her “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’sDuel in the Sun (1946)”, the marriage symbolizes the “integration into the symbolic” and “resolution of the Oedipus complex” (33). In this text, the happy ending signifies the femininity’s return to the symbolic order, along with the romanticization of the heterosexual relationship through Baines’ delicate caressing and kissing that nevertheless, once again, reminds Ada as well as the female spectators of the castration in themselves. The displacement of phallic attributes disappoints the search of femininity enunciation within a larger sphere that has long conformed to the practices of the Freudian-Lacanian psychoanalytic ideologies.

In addition to the aforementioned failed attempts at emancipating females from the symbolic construct and authentically representing femininity beyond erotic spectacles, The Pianocan also be seen as a consecutive process that encompasses a pre-lingual infant’s development into the symbolic order. From the moment when Stewart takes out Ada’s portrait from the pocket denoting the birth of a newborn, to Ada and Flora’s mirror shot which signifies the infant’s formation of the perceived object and subject, eventually to the post-intercourse almost-breaking-the-fourth-wall mirror gaze that amounts to (mis)recognition and narcissism, the film is an enclosed demonstration of Lacan’s mirror stage. This unification with the mirror stage essentially leads to the film’s subscription to the patriarchal order generated from the Oedipal complex. Together with the inauthentic empowerment of femininity as in the previous discussion,the film itself is inadequate to address the post-structural notion of emancipating from the symbolic order to attain a feminist ideal, in spite of the notable amount of affection it has brought about among the female audience. It is precisely the intelligent yet obscure aesthetic of female representation deviating from the mainstream’s habitual adoption of female specificity that connotesThe Piano’s uniqueness as a film positioned at the cusp between mainstream and its counterpart.

Naturally, an associated question is raised as to whether it is acceptable for feminists to have feelings and to be affected. A similar notion is briefly examined in Anu Koivunen’s “The Promise of Touch: Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory”. The way that the female spectators affect and are affected by the texts unavoidably escorts them in the direction of submitting to the Law of the Father due to the symbolic lack, objectification of Oedipal tendency and all that follows, as the symbolic order is so deeply rooted as the language itself, after all. An ideal post-structural work that authentically represents femininity would be something elusive of the male gaze with the female bodily spectacles completely excluded from the screen and the inherent maternal semiotics preserved.This can be very difficult to achieve considering not just Mulvey’s whole realization of fighting while being “caught within the language”, but also in Freud’s account of the sophistication of “the ‘phallic’ phase in girls” which “[belongs] in limbo without a place in the chronology of sexual development” (Mulvey 33). While contemplating whether females stuck in such a frustrating “phase” are permitted to feel, the complication of the struggle remains.

In fact, what really matters in this discourse is not “can or should they feel”, but rather “what to feel” and “how to feel”. What to feel refers to the means through which females feel related and affected. For instance, it is acceptable for female characters to be presented erotically provided that the term “eroticism” is not defined upon sexuality difference generated by maternal semiotics; what to feel in this case concerns female characters’ display of eroticism without alluring acts of voyeurism. The 2013 production Heris a suitable example that demonstrates a feminist text consisting of erotic “what-to-feel”s, with the female protagonist not having a physical entity but still embodying femininity attributes. On the other hand, how to feel is related to Laura Marks’ notion of “optical visuality”, acknowledged by Koivunen (105). Another term for comparison is “haptic visuality”. The two differ in terms of the distance between the spectator and the spectacle; “optical visuality” creates a conscious distance between the viewer and the spectacle and foregrounds “seeing” whereas “haptic visuality” invites the viewer to lose herself in the viewed and puts forward the sense of feeling or if you will, touching. I propose that when trying to reject the symbolic order,a feminist or female viewer should lean toward the end of “optical visuality” and remain as conscious as one can, precisely because of the struggle to fight against the order planted as deeply as language and affects may easily fall back into the unconscious order.

In conclusion, the essay proves The Pianoinadequate to enunciate femininity under the Freudian-Lacanian psychoanalytic construct and suggests a possible approach inspired by Anu Koivunen that emancipates the exploration of authentic representation of femininity from the constraints of the symbolic order.

Works Cited

Bihlmeyer, Jaime. “Jane Campion's The Piano: The Female Gaze, the Speculum and the Chora within the H(y)St(e)Rical Film.”Essays in Philosophy, vol. 4, no. 1, 2003.

Crofts, Stephen. “Foreign Tunes? Gender and Nationality in Four Countries' Reception of The Piano.”Jane Campion's The Piano, edited by Harriet Elaine Margolis, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 135–162.

Klinger, Barbara. “The Art Film, Affect and the Female Viewer: The Piano Revisited.”Screen, vol. 47, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2016, pp. 19–41.

Koivunen, Anu. “The Promise of Touch: Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory.” Feminisms, edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers, Amsterdam University Press, 2015, pp. 97–110.

Mulvey, Laura. “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ Inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun(1946).” Visual and Other Pleasures, Palgrave Macmillan, 1989, pp. 29–38.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”The Norton Anthology and Theory and Criticism, edited by Vincent B Leitch, W. W. Norton, 2001, pp. 2181–2192.

View more about The Piano reviews