Excerpted from the film critic collection "Movies in My Life" published by Truffau in 1974, English translation: American edition published by Leonard Mayhew Da Capo Press. The film that Truffau saw that year was not the rebuilt version of 1998 that is now widely circulated, but the version edited by Universal at that time and is not recognized by Wells. Now we find that the first thing we did in the rebuild in 1998 was to remove the opening subtitles and complete the idea of Truffaut in the first sentence of this article.

You could remove Orson Welles's name from the credits and it wouldn't make any difference, because from the first shot, beginning with the credits themselves, it's obvious that Citizen Kane is behind the camera.

Touch of Evil opens on a shot of the clock of a time bomb as a man places it in the trunk of a white car. A couple have just gotten into the car and started off, and we follow then through the city. All this happens before the film starts. The camera perched on a motorized crane loses the car, finds it again as it passes behind some buildings, precedes it or cataches up with it, right up to the moment when the explosion we have been waiting for happens.

The image is deliberately distorted by the use of a wide-angle lens that gives an unnatural clarity to the backgrounds and poeticizes reality as a man walking toward the camera appears to advance ten yards in five strides. We're in a fantasy world all through this film, the characters appearing to walk with seven-league boots when they're not gliding on a moving rug.

There are movies made by incompetent cynics, like The Bridge on the River Kwai and The Young Lions, movies that are merely bluff, designed to flatter a public which is supposed to leave the movie house feeling better or thinking it has learned something. There are movies that are profound and lofty, made without compromise by a few sincere and intelligent artists who would rather distrub than reassure, rather wake an audience up than put it to sleep. When you come out the Alain Resnais' Nuit et Brouillard, you don' t feel better, you feel worse. When you come out of White Nights or Touch of Evil, you feel less intelligent then before but gratifies anyhow by the poetry and art. These are films that call cinema to order, and make us ashamed to have been so indulgent with cliche-ridden movies made by small talents.

Well, you might say, what a fuss over a simple little detective story that Welles wrote in eight days, over which he didn't even have the right to supervise the final editing, and to which was later added a half-dozen explanatory shots he'd refused to make, a film he made "to order" and which he violently disavowed.

I'm well aware of that, as well as that the slave who one night breaks his chains is worth more than the one who doesn't even know he's chained; and also that Touch of Evil is the most liberated film you can see. In Barrage contre le Pacifique, Rene Clement had complete control; he edited the film himself, chose the music, did the mixing, cut it up a hundred times. But Clement is a slave nonetheless, and Welles is a poet. I warmly recommend to you the films of poets.

Welles adapted for the screen a woefully poor little detective novel and simplified the criminal intrigue to the point where he could match it to his favorite canvas------the portrait of a paradoxical monster, which he plays himself----- -under cover of which he designed the simplest of moralities: that of the absolute and the purity of absolutists.

A capricious genius, Welles preaches to his parishioners and seems to be clearly telling us: I'm sorry I'm slovenly; it's not my fault if I'm a genius: I'm dying: love me.

As in Citizen Kane, The Stranger, The Magnificent Ambersons, and Confidential Report (ie "Mr. Arkadin"), two characters confront each other------the monster and the sympathetic young lead. It's a matter of making the monster more and more monstrous, and the young protagonist more and more likable, until we are brought somehow to shed real tears over the corpse of the magnificent monster. The world doesn't want anything to do with the exceptional, but the exception, if he is an unfortunate, is the ultimate refuge of purity. Fortunately, Welles's physique would seem to preclude his playing Hitler, but who's to say that one day he will not force us to weep over the fate of Hermann Goering?

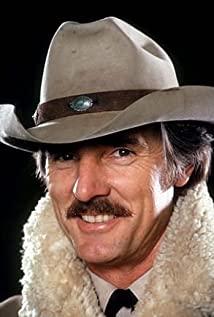

Here Welles has given himself the role of a brutal and greedy policeman, an ace investigator, very well known. Since he works only by intuition, he uncovers murders without bothering about proof. But the court system, which is made up of mediocre men, cannot condemn a man without evidence. Thus, Inspector Quinlan/Welles develops the habit of fabricating evidence and eliciting false testimony in order to win his case, to see that justice will triumph.

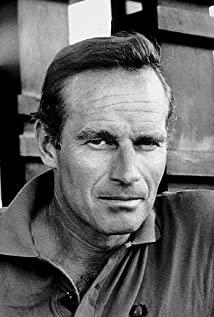

After the bomb explodes in the car, all that necessary for everything to go awry is for an American policeman on his honeymoon (Charlton Heston) to meddle in Quinlan's investigation . There is a fierce battle between the two men. Heston finds proff against Welles while Welles manufactures evidence against him. After a frantic sequence in which Welles demonstrates that he could doubtless adapt de Sade's novels like nobody else, Heston's wife is found in a hotel , nude and drugged, and apperently responsible for the murder of Akim Tamiroff, who in reality has been kiledd by Quinlan------whom Tamiroff had naively helped set this demonic stage.

As in Confidential Report, the sympathetic character is led to commit an underhanded act in order to undo the monster: Heston records the few decisive sentences on a tape recorder, sufficient proof to destroy Welles. The film's idea is summed up neatly in thie epilogue: Sneakiness and mediocrity have triumphed over intuition and absolute justice. The world is horrifyingly relative, everything is pretty much the same------dishonest in its morality, impure in its conception of fairness.

If I've used the word monster a number of times, it's merely to stress the fantastical spirit of this film and of all Welles's movies. All moviemakers who are not poets have recourse to psychology to put the spectator on the wrong scent, and the commercial success of psychological films might seem a good enough reason of them to do this. "All great art is abstract," Jean Renoir said, and one doesn't arrive at an abstraction through psychology------just the opposite. On the other hand, abstraction spills over sooner or later onto the moral, and onto the onlt morality that preoccupies us: the morality that is invented and reinvented by artists.

All this blends very well with Welles's supposition that mediocre men need facts, while others need only intuition. There lies that source of enormous misunderstanding. If the Cannes Film Festival had had the wisdom to invite Touch of Evil to be shown rather than Martin Ritt's The Long Hot Summer (in which Welles is only an actor), would the jury had the wisdom to see in it all the wisdom of the world?

Touch of Evil wakes us up and reminds us that among the pioneers of cinema there was Melies and there was Feuillade. It's a magical film that makes us think of fairy tales: "Beauty and the Beast," "Tom Thumb," La Fontaine's fables . It's a film which humbles us a bit because it's by a man who thinks more swiftly than we do, and much better, and who throws another marvelous film at us when we're still feeling under the last one. Where does this quickness come from, this madness, this speed, this intoxication?

May we always have enough taste, senstivity, and intuition to admit that this talent is large and beautiful. If the brotherhood of critics finds it expedient to look for arguments against this film, which is a witness and a testimony to art and nothing else, we will have to watch the grotesque spectacle of the Lilliputians attacking Gulliver.

- 1958

View more about Touch of Evil reviews