The issue that Hannah Arendt has repeatedly discussed, to put it more vulgarly, is actually the issue of "indirect killing", or unintentionally killing.

The originality of Hannah Arendt lies in the fact that the candle shed light on one of the most important and complex issues in the 20th century, namely the organization and institutionalization of murder: when the totalitarian (actually including some capitalists) ) decompose the killing order into a set of sub-orders that the bureaucracy can understand, which is issued layer by layer, sub-contracted, and the specific executor--perhaps only the executioner at the end--can claim no responsibility (as Eichmann claimed). I just put the Jews on the train), and my conscience will not be questioned. For them, executing part of the killing order is no different from executing the annual production plan issued by their superiors.

So the problem becomes how to judge these mundane bureaucrats, these mediocrity who never think independently. As the film says, you can't, and you can only judge individuals; because you can't judge history. Even if you go back to the top decision maker, you may not be able to conclude that he was personally responsible for the disaster (which cannot be discussed here) - this is precisely the complexity of the "indirect killing" problem that Arendt has devoted his life to researching. totalitarianism, the cause of evil.

As Arendt said in the film, the Western traditional concept believes that evil is caused by selfishness and evil is intentional; and this concept cannot explain Nazism and anti-Semitism. For ordinary people (including many of Arendt's friends), it is most convenient to blame the evil on the Eichmanns. This binary "them/us" narrative has and will continue to shape the Jewish national narrative.

The preciousness of Arendt, which is also not easily understood by the times, is that she is not satisfied with verbal criticism and moral judgment, but wants to "understand" (she argues that this is not "defense" or "forgiveness"); I don't want to be limited to thinking as a "Jew", but want to think from a "human" perspective. This is not because she wants to pretend to be astonishing, or intellectual arrogance, as many people have criticized, but because of her status as a philosopher and an intellectual. Maybe there are other thinkers who think like her, but lack the passion and courage to provoke public outrage.

And the resilience of her intellectual legacy is astonishing. One of the major contributions of 20th century political thinkers is dystopia, and Arendt's originality lies in bringing the reflection of utopia to the reflection of the evil of mortals. On this basis, she called for a return to the tradition of classical republicanism and advocated the virtue of civic participation.

As Arendt said, the friend of "banal evil" is numbness, obedience, and giving up thinking, while the enemy is conscience, the concept of right and wrong. The problem that fascinates her is that most of the enforcers under the totalitarian system are not ideological frenetic. What makes them give up thinking is their lazy loyalty to the country and the head of state, and the inertia of entrusting their mediocre self to a "system" that seems to be much stronger than themselves: when party members and bureaucrats cannot understand the instructions they receive , they are not accustomed to questioning the order itself, but are disgusted by the "disloyalty" in their own minds, doubt their ability to judge problems, and choose to believe that the organization above always sees them higher and farther than them, I have no choice but to perform faithfully. And when the consequences of the disaster emerge completely and unmistakably, they can easily forgive themselves, because people did not kill them directly, and their actions are still far from the final consequences of the disaster - the fine division of labor in the modern bureaucracy, the stacking of bed frames The power system of the house provides justification for this justification, so individuals can hide behind the system and kill people with peace of mind.

This is precisely the tragedy of 20th/21st century politics. Murder is no longer the behavior of the ancient vicious robbers, but can be embodied in many forms--does the production and sale of fake medicines and fake milk count as murder? Are casualties due to neglect of management in detention centers and prisons counted as homicides? Does neglect of care in a nursing home cause the death of an elderly person count as homicide? Insufficient prevention and control of infectious diseases leads to large-scale infections that are not considered murders? And how many of the little screws in each system feel like they've killed someone? Will he repent for his sins for the rest of his life?

Arendt has astutely dug into this question. Unfortunately, this problem never stopped.

-------------

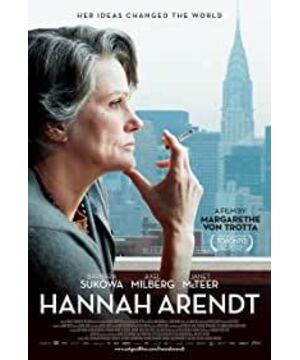

Just a word about the movie itself. This is a very intellectual film.

The protagonist is an intellectual, and there are not many action scenes, focusing on dialogue, debate, and writing. It can be seen that the director put a lot of thought into moving the picture, the transformation of time and space, and the creation of conflict, but the topic itself is still The audience is destined to be limited. Of course, the threshold has been lowered a lot compared to Arendt's original work, but basically there are still a small number of people who are interested in watching it.

Those who are interested can compare it with "The Reader". The latter is also a matter of banal evil, but in the story of a real little man. The visibility is much stronger and more popular. Movies with intellectuals as the protagonists are always difficult to make, so I really want to give a thumbs up to the creators.

View more about Hannah Arendt reviews