The text is transferred from: Hong Kong martial arts, the "softness" and "rigidity" of action movies - from "Drunken Man" and "One-Armed Swordsman" - Li Jun - Film Literature Invasion and Deletion

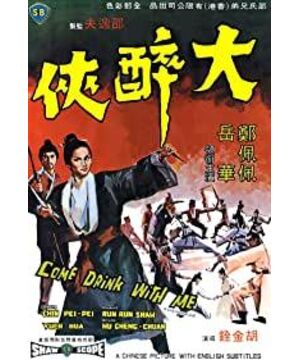

In the 1960s, "The Drunken Man" (1966) directed by Hu Jinquan and "The One-Armed Swordsman" (1967) directed by Zhang Che became the new benchmarks of Hong Kong martial arts movies, or the beginning of "the new century of Hong Kong martial arts movies". The two films by the two directors have injected Hong Kong martial arts films with author characteristics that are different from those of the past. As the most localized part of Hong Kong genre films, martial arts films and Hong Kong films have experienced a certain evolution of modernity since the 1960s, and "The Drunken Man" and "The One-Armed Swordsman" may be the evolution of this modernity. starting point.

1. Use "softness" to overcome "hardness"

In 1966, the opening scene of "The Drunken Man" directed by Hu Jinquan featured a jade-faced fox in white, played by Chen Honglie, and Yue Hua also played the role of Fan Dabei as an actor who signed with Shaw Brothers, but the core protagonist of the film But it is not these men, but Jin Yanzi played by Zheng Peipei. If it is said that in the imagination of Chinese martial arts cultural tradition, "Jianghu" has always been a world of some kind of male order, then the Hong Kong martial arts film director represented by Hu Jinquan has injected a kind of "feminine" tradition into the imagination of "Jianghu". In Hu Jinquan's films, the image of "women" is strengthened, and female characters are more involved in the narrative of martial arts stories. From "Golden Swallow" played by Zheng Peipei in "Drunken Man", to Zhu Hui played by Shangguan Lingfeng in "Dragon Inn" (1967), to Yang Hui played by Xu Feng in "Chivalrous Girl" (1971). .. The image of the "female hero" shaped by Hu Jinquan has been deeply rooted in the hearts of the people. In the film "Drunken Man", we see that Jin Yanzi played by Zheng Peipei is dressed in short clothes and holds a pair of knives. His eyes are full of heroic brows, and his body is more flexible. Faced with a group of five big and three thick men, surrounded by men. One against ten. This image of a "female hero" who challenges the male order is itself modern.

Director Hu Jinquan set up two wonderful action scenes in the development section of "The Drunk Man", which took place in the inn and the ancient temple respectively. Such gender imbalances and spatial arrangements are dramatic. In the "Jianghu" imagination of the Chinese martial arts culture tradition, the inn is one of the few social public spaces in ancient China, and it is also a world of male order, full of the discourse of male power, and the presence of women is absent here. Hu Jinquan made the female body appear in the inn scene, confronting a group of male bodies and gaining the upper hand in the fight, this powerful female image is shocking to the world. If we say that the "Huangmei Diao Movie" represented by Li Hanxiang has launched many female stars in the film practice of the 1950s and 1960s before Hu Jinquan, strengthened the role of female characters, and established the "negative" image of Hong Kong costume films. Tradition, then, what Hu Jinquan brings is a new gender aesthetic that is different from the past.

The "female hero" image in Hu Jinquan's films has both a female body and a masculine temperament. It is not only "feminine", but also has a certain gender resilience. As an intruder, destroyer, and protester of a male power order, the female body first takes on the mantle of her opposite in terms of external decoration. Zheng Peipei, Xu Feng, Shangguan Ling... These actresses are not only handsome in appearance, but often disguised as men when they first appeared. They are stripped of the feminine side of their female bodies, and instead participate in the "Jianghu" imagination of martial arts movies in a relatively neutral image. The potential male voyeuristic sight created by the "feminine" tradition of Hong Kong costume films since Li Hanxiang has to be interrupted here: what is presented on the screen is no longer a female body that welcomes and obeys male desire, but confronts male sight "Woman". This is a new gender aesthetic style that Hu Jinquan has led since "The Drunk Man". .

In addition to the intuitive aspects such as clothing and images, the identity setting of female images in Hu Jinquan's films also constitutes a unique type. They often appear at the breaking point of the male power order and appear as male saviors or avengers--- - Jin Yanzi in "Drunken Man" is her brother's savior, Yang Huizhen in "Chivalrous Girl" is in charge of killing her father; The "female heroes" in the 2000s have hatred for the family and the country, and they have a deep sense of righteousness... This is also a profound break with the "jianghu" imagination of traditional martial arts movies. Hu Jinquan, who is familiar with the history of Ming Dynasty, likes to use the chaotic background of that particular era as the historical time and space, which is more helpful to shape the images of women in his stories who are outside the male order. The female warriors in "Storm in Yingchun Pavilion" and "Empty Mountain and Spiritual Rain" (1979) are themselves walking people, and this status also allows them to freely stray from the male order.

However, Hu Jinquan, who pays attention to "femininity", is not a feminist in the modern sense. The appearance of "female heroes" in many Hu Jinquan movies is only an occasional supplement to the "jianghu" imagination of martial arts movies as a male order. In Hu Jinquan's martial arts stories, whether or not those stories are directly centered on "women's heroes", they are ultimately inseparable from the dominant position of men. Just as Jin Yanzi in "The Drunken Man" cannot do without the help of Fan Dabei played by Yue Hua, the "female heroes" in many Hu Jinquan films inevitably turn to men and finally convert to the "jianghu" of the male order. For Hu Jinquan, the tradition of "femininity" is not a gender ratio at the narrative level, but a film aesthetic in a broader sense. It is reminiscent of director Hu Jinquan's profound Chinese classical culture.

The opening paragraphs of the film "Empty Mountains and Spiritual Rain" are breathtaking. Before that, we may have never seen a martial arts movie before the main characters and main scenes, which simply lays out the landscape, time and space of Chinese martial arts "Jianghu". One after another, the landscape-like vistas appear, and the figures seem to be wandering in Chinese paintings until they enter the ancient Buddhist temple. The ancient temple and bamboo forest scenes in the film "Chivalrous Girl" have become classics in the history of Chinese martial arts films. Hu Jinquan pioneered the use of the soft texture and deep light and shadow of the bamboo forest. Compared with those fighting scenes in Zhang Che's films, where the body is exposed at every turn, the characters in Hu Jinquan's films are relatively more reserved, and the fights dressed in elegant ancient Chinese costumes are more classical.

In terms of charm, the martial arts and action films directed by Tsui Hark can be called the successors of Hu Jinquan. Tsui Hark's unrestrained imagination and originality are reflected in the costumes, shapes, sets and art of a movie like Jinquan Hu. The 1990 version of "Swordsman" became a symbol of this inheritance relationship: the film was directed by Hu Jinquan, and the executive directors were Tsui Hark, Cheng Xiaodong, and Li Huimin. And Tsui Hark's 1992 work "New Dragon Inn" (directed by Li Huimin, Cheng Xiaodong, Tsui Hark) is a direct remake of "Dragon Inn". But this article pays more attention to the "femininity" in Tsui Hark's films. Just like his predecessor Hu Jinquan, in the practice of film creation more than 20 years later, Tsui Hark boldly created a group of modern "women" group portraits in his works, such as Maggie Cheung in "New Dragon Inn" Played gold inlaid jade. The 1986 film "Knife Horse" is also one of the transformation works of Brigitte Lin's screen image. This pure and sweet idol actress in Taiwan Qiong Yao's works in the 1970s gradually sought self-breakthrough, and began to try neutralization in martial arts and action movies. gender image. Her screen image of women disguised as men has been injected with richer connotations in the context of the new era.

From Tsui Hark's first New Wave directorial work, "Butterfly Change" (1979), his film narratives seem to be inseparable from a background of some troubled times. And the "chaos" of this chaotic world comes from both a dislocation of time and space background, and a dislocation of a certain identity—including gender identity . In 1992, Brigitte Lin played the undefeated image of the East in "Swordsman: The Invincible East", which became a new breakthrough for her. This time, Brigitte Lin's gender identity on the screen was no longer a woman disguised as a man, but a man. Asexual images of women, men and women. Through this arrogance of gender identity, Tsui Hark has completed his fantasy of martial arts "Jianghu", which is a world after the collapse of the old order. In 1995, the film "Knife" produced by Tsui Hark on the eve of the return of Hong Kong was a remake of Zhang Che's film "One-Armed Knife", which once again created a chaotic background, a fatherless world. Beneath the film's out-and-out male hormone hype, the story is interspersed with a female narrator, the master's daughter. She is not the protagonist of the story, but stitches the whole male-protagonist story into a female perspective. The masculine beauty of men is expressed by women's "feminine" words, under the care of women's tender and soft eyes. The gender line of sight has changed from "seeing" for men to "being seen" for men -- this film seems to be a portrayal of the fate of the entire Hong Kong martial arts and action movies.

Compared with the classical Chinese charm of Hu Jinquan's films, although many of Tsui Hark's films can be shot directly in mainland China, the space-time imagination of his martial arts "Jianghu" is farther and farther away from the real Chinese history. The various dislocations of time, space and identity are similar to those of other contemporary Hong Kong directors. Since the 1970s, their works have been in a delicate game between Hong Kong localization efforts and Chinese imagination. In terms of female images, Tsui Hark also ingeniously created more images of female ghosts and banshees in his works. The "A Chinese Ghost Story" series directed by Cheng Xiaodong, who has worked with Tsui Hark for many years, was born out of martial arts films and surpassed the traditional martial arts movie genre. Its martial arts action style design deliberately weakens the sense of strength and highlights the elegant dance form, which is also the tradition of "femininity" . Interesting appearance.

2. Use "rigidity" to control "softness"

Zhang Che's "One-Armed Swordsman" came out a year later than Hu Jinquan's "Drunken Man", but Zhang Che's pioneering contribution to Hong Kong martial arts films is no less than Hu Jinquan's. Zhang Che's works are far more numerous than Hu Jinquan. The influence on the martial arts film tradition is even greater than that of Hu Jinquan. Compared with Hu Jinquan's cultivation of Chinese classical culture, Zhang Che represents the westernization efforts of Hong Kong filmmakers. The film "One-Armed Swordsman" is more like a Hollywood movie with Chinese costume faces in terms of audiovisual form, script, and dialogue. The extensive use of Western soundtracks in the film makes "One-Armed Swordsman" different from the previous forms of martial arts films, especially the sense of drama in ancient costume films since "Huangmei Diao". As mentioned earlier, martial arts movies are an imaginary "world", and Hong Kong martial arts movies reflect the complex cultural form of Hong Kong as a city where Chinese and Western cultures blend.

Speaking of Zhang Che, the "masculine aesthetics" of his martial arts films cannot but be mentioned. If, in his martial arts films, Hu Jinquan established an imagination of a 20th-century Hong Kong-style new woman through the emergence of more "women" images. This new woman is resolute and neutral, which interrupts the The male voyeuristic sight woven by traditional films has opened a certain revolution in film viewing. Then, Zhang Che's "masculine aesthetics" completely subverts the tradition in another way by means of the male body toned, and completes the direction of gender sight. conversion. But whether it is Hu Jinquan or Zhang Che, women's bodies or men's bodies, the martial arts films in the original practice of Hong Kong filmmakers all reflect the complex modernization process and modernity imagination of the city of Hong Kong.

Hu Jinquan created a generation of female stars such as Zheng Peipei, Xu Feng, Shangguan Lingfeng and other "women heroes" on the screen. Then, Zhang Che successively introduced Wang Yu, Luo Lie, Jiang David, Di Long, Li Xiuxian, Fu Sheng, etc. in his works. male celebrity. Zhang Che's films are 100% male stories, leaving little scene for women. The friendship and value between men are the highest values pursued by his male heroes, while the love between men and women takes the second place. "One-Armed Swordsman" is based on Jin Yong's novel , a broken knife, a broken score, a broken arm, a fatherless son, the protagonist Fang Gang played by Wang Yu turned away from his master, the hero made a comeback after a disaster, and saved the master. Fang Gang and Xiaoman and Qi Pei's story. Triangular relationship... This constitutes a classic prototype in the history of Hong Kong martial arts films, and also lays the foundation for the main features of Zhang Che's martial arts films in the later works and the main connotation of Zhang Che's "masculine aesthetics".

Zhang Che's "masculine aesthetics" is first reflected in his belief in the traditional male order and its values. Fang Gang is undoubtedly a model of traditional Chinese male image of justice and integrity. In Fang Gang's mind, the love and kindness of his father and master are far more important than others, so Zhang Che seems to be conservative. But he also expressed his doubts about the traditional order to a certain extent through the attitude of the character Xiaoman in the play. "The One-Armed Swordsman" ended with the escape of "hero". After Fang Gang saved the master, he was far away from Xiaoman. Traveling to the end of the world, at the same time, Master Qi Rufeng also broke the Qimen sword. For Zhang Che, the traditional "Jianghu" order seems to be a knot that needs to be abandoned. After telling the story of a traditional "Jianghu" in the time of the whole movie, Zhang Che left the world with a "hero" turning back.

Zhang Che's "masculine aesthetics" is more intuitively reflected at the physical level. After Zhang Che, Hong Kong martial arts movies and later action movies gradually became keen to show the toned body of naked men. Zhang Che even created a series of corresponding audio-visual languages in terms of lighting, tone, color and other forms. Zhang Che was paranoid and obsessed with the effect of blood dripping from his body. He was once mocked as the "director of tomato juice" and criticized for instigating violence. Violence has gradually become the main selling point of Hong Kong martial arts and action films. The extreme representation of the male body on the screen also constitutes a unique symbol. Beginning with Wang Yu, the martial arts students in Zhang Che's films are all strong, muscular, with an inverted triangle shape and clear muscle contours. When the heat was in full swing, the hot-blooded men on both sides went into battle shirtless, and when the sword went down, blood must be seen, accompanied by exaggerated screams. Zhang Che has also created images of mutilated limbs many times. In addition to "The One-Armed Swordsman", in "Thirteen Taibao" (1970), the scene of Li Cunxiao played by David Jiang was the most brutal in history.

This fascination with the body was inherited by Bruce Lee's films after the 1970s. The tradition of Hong Kong costume martial arts films was inherited and improved by Hong Kong action films. An imagination of "Jianghu" has transformed into an imagination of the body, "Jianghu" The myth of ' morphs into the myth of the body. Bruce Lee, both on and off the screen, is a complex of multiple imaginations and myths for fans. His toned physique and his physical confrontation with Orientals and Westerners on the screen have rebuilt the national confidence of the Chinese people, and more precisely, the confidence of the Hong Kong people. The ancient costume martial arts films under the label of Shaw Brothers have fallen behind the times since Bruce Lee appeared. Hong Kong, which is thriving on the banks of Victoria Bay, is a fantasy city that eagerly embraces the West and embraces modern imagination. In Bruce Lee's films, physical combat is preserved, but the spatial background presented by Bruce Lee's films has undergone a major replacement. From "Big Brother Tangshan" (1971, "Jingwumen" (1972) to "Dragon Crossing the River" (1972, "Dragon and Tiger Fight" (1973), Bruce Lee's film time and space focus more on the present every time. If The jumping and kicking before the martial arts hall at the end of "Jingwumen" is the Chinese people's imagination of a century of national humiliation. Then, the Chinese-Western confrontation in the Roman arena in "Raptor Crossing the River" is the Chinese people's imagination of returning to the world. In a post-colonial context, though, the toned male body of Hong Kong's martial arts, action films is destined to become some kind of signifier that is constantly being groomed by all kinds of imaginings. It's modern, westernized: the body we adore on the screen The image is really just some kind of physical illusion of our mirror image relationship with the West.

Even with the same male body, the male images in Hu Jinquan's films are rarely exposed. The image of a long gown is more like coming out of Chinese figure paintings, and it is difficult to reveal the contours of body lines and muscles. This is an intuitive distinction between a "feminine" body and a "masculine" body. This interesting distinction appeared in the earliest works of Hu Jinquan and Zhang Che in the 1960s. If it can be said that Hu Jinquan's films more pinned on Hong Kong films' imagination of "classical China", then Zhang Che's films foreshadowed Hong Kong films' imagination of "modern West". These two different imaginations converge in the "Jianghu" imagination of Hong Kong martial arts films and in the body performance. Bruce Lee transferred the time and space of traditional martial arts movies from an "ancient costume" China to a "modern" world, and the body in Bruce Lee's works is also modern. Bruce Lee's martial arts movements are known for his fast close combat, and he is good at using personalized weapons such as nunchakus. It is more suitable for street battles in small spaces in urban streets, such as several street battles in "Raptor Crossing the River", the more narrow the space is. Being cramped, the martial arts action design of Bruce Lee's films is more comedic and dramatic. In this regard, the action design of Jackie Chan's films has inherited the characteristics of Bruce Lee's works, and has made many useful attempts to show the interaction between the male body and the modern urban space. After Bruce Lee, the status of Hong Kong martial arts films has actually given way to action films. Strictly speaking, these two types are actually one and two, two and one relationship, and the distinction is not strict. Many directors who made martial arts films in Hong Kong also made action films, and directors who made action films also made martial arts films. Both types are continuing the "Jianghu" imagination of Hong Kong movies. In 1971, the 25-year-old John Woo joined Shaw Brothers and followed Zhang Che to make movies. For two years, he has been Zhang Che's assistant director. In the 1980s, John Woo found his place in Hong Kong movies after replacing the knives in Zhang Che's films with guns. This is the era when gunfight action movies were popular. The time and space presented by Hong Kong action movies are getting closer and closer to the present, but what remains the same is the imagination of "jianghu". The feelings of "Jianghu" in Zhang Che's films were inherited by John Woo, which is a belief and defense of the traditional male order and its values. In Hong Kong, where the value of "hero" is constantly being dispelled, John Woo has created a Quixote-style "male hero" played by Chow Yun-fat as Pony Ma.

The "masculine aesthetics" of Zhang Che's films has evolved into the peak "violent aesthetics" in Woo. But the tradition of "masculine" between master and apprentice is in the same line. If there is a teacher, there must be an apprentice. The works of the two people seem to be bloody or even bloodthirsty. Zhang Che's film has a bloody body stabbed by a sword, and John Woo's film has a body that is riddled with bullets and holes. . It seems that the more tragic death is enough to make the "male hero" in the film, the two directors' works have unforgettable death scenes. From Zhang Che to John Woo, they used the length of the entire film to compose a body epic, and death is the final aria of this body epic.

3. Combining "rigid" and "soft"

The body stabbed and penetrated by swords or bullets in Zhang Che and John Woo’s films has become a symbol with multiple meanings. If the fit male body in Hong Kong martial arts films is itself an imaginary body, then this symbol first means a broken tradition order and value. In Hong Kong martial arts and action movies, we have seen too many tragic heroes in troubled times. From Zhang Che to John Woo, they all try to reproduce a certain kind of myth of the male "jianghu" order, but often what we see at the end of the myth is a myth. disillusioned. Fang Gang in "The One-Armed Swordsman" is set as a "fatherless" son. His father fell in the blood of the traditional order. Fang Gang himself still lives in the superstition of this traditional order. Faith has paid a heavy price. The broken arm is a metaphor for the brokenness of the order at the physical level, and the broken arm, broken sword and incomplete music all mean the incomplete ideal of Fang Gang, who has no father and no teacher. Fang Gang had to deviate from his teacher's family, without a father and no home, his heroic efforts at the end of the day expressed Zhang Che's inner heroism. At this time, it was the appearance of a female character who saved Fang Gang, who was in desperation. Xiaoman used the power of female "femininity" to heal Fang Gang's pain in the face of the broken order. "Masculine", like Zhang Che, also needs some kind of "femininity". Zhang Che's "Jianghu" order, a world of male power, also needs the complement of women.

Many of Zhang Che's films have left too much time and scenes to the "heroes" and men on the screen, but the power of "femininity" still exists as a narrative driving force, so we see that the male friendship in the film often occurs. Some kind of ambiguous dislocation. For example, the brothers Jiang David and Dillon have co-starred in films such as "Thirteen Taibao" (1970, "Shuangxia" (1971, "New One-Armed Swordsman" (1971), and there are almost no female roles. Especially "Double Heroes", there are no female actors at all. David Jiang and Dillon look at each other with heroic eyes on the screen, and there are no women present at all. This gender identity dislocation not only breaks the traditional "men see, women see" The model of “being seen” is not a simple inversion of the model of “women see, men are seen”. This kind of gender perspective in movie viewing is unprecedented. This dislocation of gender identity is placed in the era and political language of Hong Kong. There are also many metaphors at a deeper level. As martial arts and action films are a kind of "jianghu" imagination, the bodies of these male actors are an imaginary body, and the dislocation of their gender identity itself means that Hong Kong is facing The complex mirror relationship between "modern West" and "traditional China". The body in martial arts movies is like the body in the mirror. In the mirror, Hong Kong sees both the other and the self, and when facing the mirror, it is lost in confusion. its own subjectivity.

As a unique type of Hong Kong martial arts and action films that interpret the male "jianghu" imagination, the gender imbalance brings some interesting new reconciliation, the friendship between men replaces the love between men and women, which is "feminine" The side of Hong Kong is common in the narratives of Hong Kong martial arts and action films. From the beginning of Zhang Che's works, John Woo can be called the new successor of this "combination of rigidity and softness" in the 1980s. In the mature period of John Woo's personal style, the works "The True Color of Heroes 1" (1986, "The True Color of Heroes 2" (1987, "Blood Two Heroes" (1989, "Across the World" (1990) .... This kind of male-to-male gaze structure film narrative. Shaped Chow Yun-fat and Dillon in "The True Color of Heroes" and Chow Yun-fat and Li Xiuxian in "Blood", Chow Yun-fat and Zhang Yinrong in "Across the World", these golden combinations in John Woo's films, Brother partner. Like Zhang Che's martial arts films, there are not many women in these shootout action films. Whether in or outside the film, women are destined to miss this world of swords and swords, guns and fire. This is a kind of film Men inside and outside look at the narcissism of men. Hong Kong is imagining the imaginary body in the mirror world in the imaginary "jianghu". John Woo's imaginary body is derived from his master Zhang Che, and he goes further than Zhang Che. It is becoming more and more Westernized and Hollywood-oriented. We can see more and more of John Woo's Hollywood imagination, both in the physical and spatial aspects of the film.

After the first and second parts of the "True Colors of Heroes" series were produced, the third "True Colors of Heroes 3: Song of the Sunset" was directed by Tsui Hark. As mentioned earlier, Tsui Hark generally still belongs to the "feminine" sequence in the tradition of Hong Kong martial arts and action movies. After he took over this drama full of male hormones, he changed his face and placed it in the male world. A female "king".---- Zhou Yingjie, played by Anita Mui, once again conquered all male partners on the screen with a relatively neutral female image. But martial arts and action movies were still dominated by men in the 1980s. In terms of martial arts films, Liu Jialiang can be regarded as a representative of hard-line martial arts in the 1980s, such as "North and South Shaolin" directed by Liu Jialiang in 1986. In terms of action films, in addition to John Woo, Lin Lingdong's "Prison Storm" (1987, "School Storm" (1988), MacDonald's "Province and Hong Kong Flag Soldiers" (1984, "Provincial and Hong Kong Flag Soldiers" sequel ” (1987), also publicized a strong masculine and masculine emotion, and both have strong humanistic feelings.

The myth of "Jianghu" in the 1990s was continued by a new generation of Hong Kong filmmakers, but they had to face a new and unprecedented context of the times. Liu Weiqiang and Wen Jun's "Young and Dangerous" series created typical images such as Hao Nan played by Ekin Cheng and pheasant played by Chen Xiaochun. In this series of movies adapted from street comics, the law and order situation in Hong Kong seems to be lawless. Boys" can block the entire road at every turn, and the friendship between men and men has once again been mentioned to a certain level of ignorance. The "Young and Dangerous" series has the space of a modern Hong Kong metropolis, but still weaves the outdated "Jianghu" myth and male order. In the 1990s, the "Jianghu" of Hong Kong martial arts and action films was over-idealized and romanticized. Compared with Liu Weiqiang, To Qifeng's films are more sensitive, witty, and more profoundly capture the political context of Hong Kong before and after "97", and the "Jianghu" imagination is more symbolic and allegorical.

From the film "Dark War" (1999), it can be seen that To Qifeng is no longer obsessed with the male order imagined in the traditional "jianghu", and the confrontation between the police and the bandit is interpreted as a 72-hour game of wits and bravery. A male body game. The bandit played by Andy Lau and the policeman played by Liu Qingyun are actually both enemies and friends. The confronting two sides are no longer incompatible enemies, but two bodies that compete with each other, two personalities that admire each other. The films "Gun Fire" (1999, "Exile" (2006) even more publicized To Qifeng's male heroism. In a troubled world with no father, no home and no country, the heroes of the apocalypse cherished each other and cherished each other's past. The despised traditional order and its value. The male body in Johnnie To's films is once again faced with the dilemma of identity dislocation due to its incompatibility with the context of the current era. This dilemma is also faced by today's Hong Kong movies and even today's Hong Kong. During the same period and in the same context, we also repeatedly saw identity dislocations from gender, space, symbolism, imagination, etc. in the films of Guan Jinpeng and Xu Anhua. Later, we saw the new generation in Peng Haoxiang's films. Filmmakers' mockery of male "Jianghu". In Chen Guo's films, I see another kind of "Jianghu" imagination that looks at the current urban space of Hong Kong, especially the social space at the bottom.

Finally back to martial arts movies. After the 1990s, Wong Kar-wai and Ang Lee each directed a film that was both a martial arts film and not a martial arts film, completing its modern transformation from the form to the content of this ancient genre of Hong Kong cinema. Wong Kar-wai's "Evil in the East" (1994) and Ang Lee's "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" (2000) can be said to be the gods who express the erotic stories of modern men and women in the form of traditional martial arts stories. Ang Lee also invited Yuan Heping as the martial arts director of his film, but here, the movement itself is not the most important, and the movement becomes the starting point of multiple meanings. When Yu Jiaolong (played by Zhang Ziyi) and Li Mubai (played by Chow Yun-fat) are jumping and moving on the branches of the bamboo forest, you advance and I retreat, what we see is a game between a male body and a female body, and more importantly, individual lust and thousands of years. The game of traditional Chinese order. This "Jianghu" imagination is not only Hu Jinquan's "Jianghu", but also Zhang Che's "Jianghu" and Li An's "Jianghu".

View more about Come Drink with Me reviews