Francisco Goya (1746-1828), Spanish painter. If Wikipedia's description of him is correct (sorry I don't know the artist at all), we may be able to apply a familiar comment and call him the last painter of the old era and the first painter of the new era. The fact that he was also classified as Romantic by art historians as a court painter for the old Spanish royal family is enough in itself to generate interest in his relationship to one of the biggest romantic storms in European history, the French Revolution. . In the film, Napoleon, the incarnation of the Revolution, appoints his brother Joseph as the new king of Spain. When the new king reviewed the relics of the previous dynasty, he expressed Napoleon's appreciation for Goya's style of painting.

The beginning of the film is chosen in 1792, the year when the Great Revolution reached its climax, in which the French King was sent to the guillotine. In the face of unrest, the Spanish Inquisition reopened. On the advice and impetus of Brother Lorenzo, the Church, which has executed only eight people in the past fifty years, is now dealing harshly with heretics, especially Judaism, Protestantism and Voltaire. In this way the so-called Enlightenment is associated with Judaism and Protestantism. Ines, the daughter of a wealthy businessman who was a model for Goya, was persecuted for being suspected of being Jewish, even though her family had converted to Catholicism several generations ago. At her father's entreaties, Goya facilitated Lorenzo's visit to the rich merchant's family dinner. The cultivator did not know that in addition to the large remuneration, the rich businessman also prepared a trap for him. Lorenzo experienced the torture of the Inquisition firsthand. God didn't give him the strength to resist pain, and he signed an absurd confession. Taking this as a threat, the wealthy businessman asked Lorenzo to find a way to free his daughter. However, the church accepted donations from wealthy businessmen but refused to release Ines. A helpless Lorenzo raped Ines before the rich businessman released the confession and fled to France. The church burned Goya's portrait of Lorenzo. Amid the flames and the din of the crowd, Goya suffered hearing problems. By the time, fifteen years later, the belated Revolution was finally delivered under the guns of Napoleon, the painter was completely deaf. And the one who brought the French was actually Lorenzo, who absconded back then. Now he has transformed himself into a faithful believer in the Revolution and Voltaire. Under the promise of the new world, the Catholic Church was banned, the monks were sentenced, the prisoners in the inquisition were released, and Ines was seen again. By the way, Natalie's "disfigurement" is far more than any actress I've ever seen, and I was really taken aback when she walked out. Her family had been killed in the war, so she had to find the only one to rely on, Goya, and ask him to find her daughter who was born in prison. Goya went to Lorenzo for help, but when the latter found out that the child was his own flesh and blood, he certainly did not want the old scar to be uncovered. Ines was sent to the lunatic asylum by him. While sketching, Goya stumbled upon Ines' daughter, Alicia, who is now a prostitute. Goya insisted that the mother and daughter meet, but Lorenzo sent troops to capture all the prostitutes and prepare to send them to the United States. The situation has now changed. Napoleon was defeated, and the British landed from the coast of Portugal, all the way to Madrid. Lorenzo was captured while fleeing. The prostitutes were also captured by the British army, and Alicia became the new love of the British generals. Ines, redeemed from the lunatic asylum, picks up Alicia's kidnapped baby in the chaos. Confused, she took the baby as her and Lorenzo's daughter. Ironically, the British became the protectors of the Catholic Church this time, and the monks returned to power. Lorenzo was hanged and the body was dragged away in a donkey cart. Ines was in hot pursuit with the baby in his arms, and the donkey cart was surrounded by cheerful children and cheerful nursery rhymes. The old Goya hobbled after him.

The two scenes at the beginning of the film tell us what the title of the film means. For one, the monks circulated paintings by Goya, full of horrific images of evil spirits. The monks were incensed by these indecent paintings, except for Lorenzo. This is a true picture of the world, he said. And the world has fallen like this, and it is the duty of the church to purge God of the wicked infidels. When he said this, he never seemed to have thought that although the church is the representative of God on earth, the world depicted by the painter is not limited to the door of this representative institution. As in the next scene, the unfinished portrait of Lorenzo has no face. Ines asked why, Goya replied jokingly, it was just a ghost. For the painter, the Church, which represents another world, is still in this world, and the monks are no different from others, and their portraits are marked with the same price. There is no one who is not a ghost in Goya's pen. The entire movie is Goya's giant scroll, and each character is a ghost.

However, this huge scroll is interrupted by an interlude. When Napoleon's army invaded Spain, we heard a first-person narration by Goya. This only occurs once in the entire movie. It seems that the painting can only express the painter's understanding of the world, but not enough to express how he came to this understanding. The mode of understanding comes from the painter's experience, and what is most unique about Goya's experience is that he relies entirely on the eye. He could not hear the rumbling of the cannons, certainly not the impassioned speeches of Lorenzo and the boiling people. Yet the painting has always been silent, and it fails to convey the uniqueness of Goya's experience. We also need the voice of the painter to understand the silence of the painting. Is it Napoleon's cannon or a speech praising freedom more representative of the Revolution? For the average person, this can be a difficult question to answer. Their ears received the shock of the cannon and the magic of speech. They were so involved in it that they couldn't watch it. For Goya, however, this is no longer an issue. He couldn't hear them, so he was immune to them. He can only see. He seems to be looking at a painting and then painting what he sees. We can imagine that the creations of the pre-deaf painters, no matter how realistic they are, can only be pseudos (pseudos) in the Platonic sense, because what the painter is trying to describe is the world in which he lives, and his experience and Paintings are different, when he uses paintings to express the world, he is using a fake to reproduce the real. A painting is a simile that admits that it is not what it wants to represent. A painting is a poem, a painter is a poet, and he knows that his painting is the lie of the Muses as if to tell the truth. Goya had Hesiodian self-knowledge. A meaningful image: the tortured Ines wailing "tell me what the truth is", and the camera turns to the scene of Goya's self-portrait. The self-portrait not only formally represents Goya's self-knowledge, but also displays the structure of this self-knowledge. When creating a self-portrait, the painter is not painting himself, but his shadow in the mirror. The shadow represents the painter himself, pointing to the painter himself, but not the painter himself. Perhaps it is such an inference of self-knowledge that distinguishes what Goya sees as the church from what it stands for.

Only two people in the film see the difference. In addition to Goya, is Ines' father. This wealthy Jewish businessman is a sophisticated businessman. Perhaps it was the omnipotent magic of money that made him see that monks were no different from ordinary people. In any case, the Ines family died in the turmoil. The usefulness of money is also limited. In peacetime, money can be turned into anything it wants, just as a Jew can convert to Catholicism. But the war was a devastating blow to the merchants. We will find, however, that the relationship between painters and merchants is more complicated than we imagined. Goya asked Lorenzo if he wanted to paint his hand in the portrait. Two thousand in one hand and three thousand in two. The painter transforms the form of the portrait according to the buyer's bid. At the same time, the painter also depicts the beauty that fascinates himself. He painted a portrait of Ines, calling her a witch with magical powers. Goya was so fascinated by her beauty that she even created the angel on the cathedral dome based on her. This reminds us of Pindar's The Isthmus Triumph Part II. Pindar juxtaposes the past with the present. At that time the Muses despised common interests, and the poet sang only what he loved; now poetry is sold (epernanto) for a reward. The Isthmus Triumph II was sold to Xenocrates, who had never met the poet. In the last conversation between Lorenzo and Goya, facing the latter's accusations, the former in turn claimed that Spain was a big brothel. An enraged Goya brought up Lorenzo's apostasy, but the former friar replied, "I have faith, and you work for a fee, and paint for whomever pays." Therefore, you are a prostitute. This leads us to think that Pindar's word "sell" (pernamai) has the same root as "prostitute" (pornē). This confusing conversation leaves our moral senses at a loss. Indeed, the warm-hearted Goya meets our standards for immorality, while the villain Lorenzo fits the image of a righteous man who devotes himself to his faith. The experience of justice again clashes strongly with the model of justice. How do we understand that a monk who betrayed his faith because of physical pain could be killed for his new faith? What happened between Lorenzo the friar and Lorenzo the revolutionary?

We still remember how, at the beginning of the film, when other monks denounced Goya as an advocate of evil, monk Lorenzo used his own eyes to prove that Goya's paintings represented the truth of the world. And according to Lorenzo, the duty of the church is to eradicate the evil that Goya discovered. He implies that the justice of the church is not an inference of theodicy, but an implementation of theodicy. In other words, theism is not a fait accompli, but is realized in the church's battle against evil. The solution, in effect, is to allow the pattern to be fully absorbed into the experience. Every experience of evil triggers a passion to conquer evil, and the conquering of evil is experienced as justice itself. The experience of righteousness is thus inseparable from the experience of evil. However, Lorenzo got it wrong, the ghost in the painter's pen is not the painter's experience, but is connected with a pattern of understanding. Lorenzo said he had seen a woman who was just like Goya's. This exposes his self-ignorance: his experience does not corroborate Goya's image, because it is not the ghostly image that corresponds to his experience, but the experience that the ghostly image evokes in him. He confuses looking at a painting with being in the world. He appeals to experience without understanding that he is understanding his experience through a certain pattern. He doesn't need to find the experience of justice to fill the pattern of justice, but he still needs to find the evil through some pattern. As he taught eyes and ears how to recognize heresy, he had to resort to methods lacking practical experience: we find an evil man not because we see him doing evil, but because he reads Voltaire, or because he calls the church holy Temple, or—in Ines' case—she doesn't eat suckling pork. Two things changed Friar Lorenzo: the desire for Ines and the lynching of a wealthy businessman. Through lust and pain, he no longer sees the world as a picture. When confronted with a painting, no experience changes the mode in which the observer understands the painting because the experience it evokes is based on that mode. However, when he encounters some kind of coercive and irresistible experience, the original mode that underpins and integrates the experience in secret breaks down. Lorenzo must have realized that it is dangerous to let experience test the pattern, it is better to use the pattern to dominate the experience and wipe out the experience that does not conform to the pattern. The light is the other side of the great revolution, and the blood during the period is nothing at all. Whether it was revenge against the church, or the intention to cover up the wrongs of the past, it has been repaired. Not surprisingly, he was not at all afraid of death, because death meant the elimination of experience. Nothing established his faith more than death. In doing so, however, Lorenzo merely re-accepted the position of his cult brothers, Ignore experience and rely solely on patterns to understand the world. The change from the revolutionary Lorenzo to the monk Lorenzo was that Lorenzo became a purer monk.

Now we realize that Lorenzo's tone was nothing more than a copy of the friar who fought him at the Holy See Council. The monks referred to Goya's models as prostitutes. For monks, prostitutes are the representative of all filth. The prostitute is just a metaphor. But now that Goya is deaf, and the "picture of the world" has changed from a metaphor to a reality, Alicia has naturally entered our field of vision. The prostitute Alicia is nothing more than bringing the metaphor of the monk into reality, she represents the truth of Lorenzo's union with Ines. Just as Alicia doesn't know her parents, the filth is a strange mixture of two ignorances. However, Alicia must have inherited a keen sense of money from her maternal grandfather. As the new love of the British general, she will be part of the coming new order. The principle of this new order is that everything can be sold. Ines took the newborn baby as her own daughter, and she never knew her daughter was a prostitute. Goya followed Ines, away from the torrent of the times. But unlike Ines, he knew the secret.

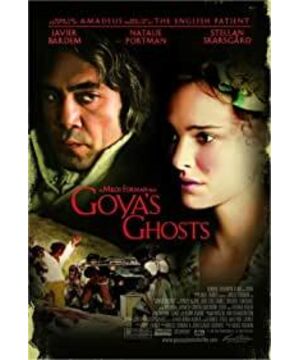

View more about Goya's Ghosts reviews