If every author and director has an obsession, then what Russian director Andrei Sarkinsev is fascinated to discuss in his works is the broken families and the post-Soviet society that sees the big from the small. Confusion and Disruption. However, after going through the obscureness of "Return" and "Exile Love" to the sharpness of "Irina" and "Leviathan", this motif continued to his fifth feature film "No Love to Tell". Unlike the richness of the earlier works, the connection between the individual and the country appears very thin, and the political implicit pattern is marginalized – a couple who are strangers but have to embark on the road of finding a child, complaining about "love" plainly, The straightforward appeal may make people marvel at the coldness of the heart in the hoarse voice, but it lacks the emotional accumulation and national feelings of the subtle, deep and poignant taste in "Return". How to make the proposition of "family, country and world" sound again and again is a breakthrough that we hope to see in Saginsev's future works. In "No Love to Tell", he did try new image expressions, using space transformation and character close-ups to present a private process of people struggling in a loveless society. So how does the director construct a loveless video world? The film opens with a bleak environment of dead trees and snow, and immediately cuts to the "small home" level: Zhenya (Marianne Spivak) and Boris (Alexey Rozin) are in a bad mood during their divorce. They agree with each other and shirk the responsibility of raising their son Alyosha (Matvey Novikov). When the two sought loving solace from their respective lovers, the son ran away angrily. While the camera recorded all kinds of verbal violence and the absence of characters without hesitation, they mockedly watched them on their second love-seeking journey and embarked on the old road of desire (lust, material desire). Zhenya bluntly said that she had never loved Boris, the combination of the two was for mutual use of survival, and the birth of Alyosha was a mistake. Therefore, marriage, blood relationship, etc. are not produced by love, and will not produce love; husband and wife break up because of lack of love, and children run away because of lack of love. So why does the film spend half its time talking about finding children? Where did the husband and wife change from "this kid really picks the time to be with us" to crying in the morgue? Was Alyosha's disappearance an opportunity for love? not at all. Life goes on indifferently, the newborn is still thrown aside, the missing person notice blurs and fades, Alyosha's room is demolished, his posters are torn down, and no one saves a thought. That lengthy search-and-rescue operation as a last-ditch effort was fleeting. From the level of "everyone", the director's points are scattered everywhere and only superficial. Surrounded by radio and TV news about doomsday, political intrigue and war, instigated and dominated by nationalism (Zhena's "Russia" t-shirt) and religious dogmatism, "Love" is frivolous and selfie Slogans and labels. But the critique that didn't go deep was just a pile of innocuous images, just like the coordinator of the search and rescue team, constantly grasping the uncertainty in Zhenya's words, sneering arbitrarily, and attacking her for neglecting the child. As for the relationship between the loveless "Everyone" and "Xiaojia", the social background of these points is a little pale and unable to really answer. The only scene that touches on this question is a confrontation with Zhenya's mother, who is known as the "female version of Stalin." Just as Elena's son and grandson spit downstairs at the beginning and end of "Irina", the class limitation of "the son inherits the father's business" is manifested in indifference and indifference in "No Love to Complain". Inheritance of hatred. Such a morbidly replicated family and an inescapable sense of powerlessness are still very visually striking. The loss of love from generation to generation predicts the disintegration of society.

In my opinion, the finishing touch of the film is the shot of several characters looking out the window. In Sarkinsev's previous works, female characters looking in the mirror as a symbol of self-examination are often used to explain the characters' behavioral motives and drive the development of the plot. For example, in "Exile Love", Vera (Maria Bonneway) felt sorry for herself in the mirror. Her husband forced her to have an abortion was the last straw that broke her faith in love, and then she ended her own life; In "Irina", Irina (Najida Marchina) stares at herself in the mirror, and finally realizes that the care she has given her husband for ten years is not as good as a sweet word from his darn daughter. In "Leviathan", Liya (Yelena Liadova) cried in front of the mirror after staying up all night, and was tortured by the indifference and humiliation of the father and son, and had the idea of suicide. In "No Love to Tell", the central scene of looking in the mirror has a new deformation and extension. At the beginning of the film, there is a close-up shot of Alyosha staring out of the window, with a calm face but with a preoccupied mind that should not be at his age. Then the camera cuts to a group of children playing football on the lawn outside the window. This is the same as the previous scene. Liao Sha throws the tape alone in the woods to create a contrast. At this moment, the lens suddenly zooms, and the lens (Alyosha's line of sight) is retracted from the window, across the window covered with rain and fog. Such a transformation of indoor and outdoor spaces reappears at the end. When the workers demolished Alyosha's room, the camera slowly advanced towards the same window until it was infinitely close to the water-stained glass window. This time the camera did not "break through" the window, but directly cut to the outside in the snow. The children (mostly accompanied by their parents) playing there, as if Alyosha were still there watching it all. What he saw was not only the world, but also himself, who had nowhere to put in the world. Why is he leaving? The cramps and restraints in the window had heralded his escape before he heard his parents arguing. However, the lack of parental love cannot be made up in the loveless society set by the director. All he broke free was this house, this family, and there was no place for him outside. He already knew this when he looked at it, but he was still determined to escape the hopelessness here. Similarly, Zhenya walked to the floor-to-ceiling window after having fun with her lover and looked out the window with the sweetness of her lover on her face. This echoes with the pregnant woman looking out the window happily and looking forward to the future at the beginning of the film. We can't help but think that maybe Zhenya and Boris were so full of love and hope at first, only to later find out that everything was false. The close-up of Zhenya looking directly at the camera at the end told herself like a mirror image, telling the audience the bitterness of life indifferently continuing.

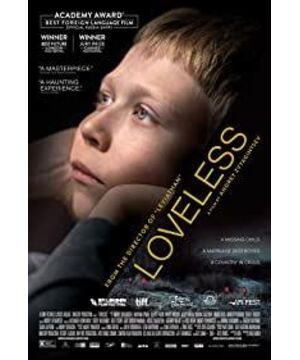

View more about Loveless reviews