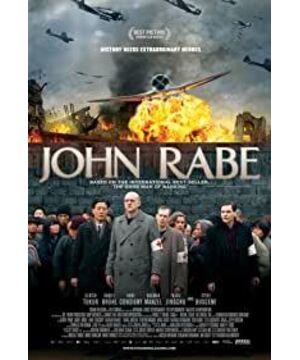

"Rabe's Diary" provides the Chinese with a new perspective on the Nanjing Massacre. The film is narrated in the first person, from the perspective of the protagonist Rabe, and closely links Rabe's personal experience with the fate of Nanjing. This approach effectively determines the choice of material for the film. Another narrative thread of the film is developed by the Japanese military's aggression process, which adjusts the overall narrative rhythm of the film while narrating from multiple angles.

There is an intriguing scene in the movie: civilians who were hit by Japanese airstrikes were sheltered under the Nazi flag. Children jumped on Nazi flags, apparently not understanding the meaning of the symbols on the flags. We can't say that the film is using human nature to "whitewash" dirty politics - although Rabe is a Nazi, it was Japanese officers who were involved in the Nanjing Massacre who later "informed". On the contrary, it actually resolved part of the political and ideological conflicts, opened a corner of the war from the perspective of human nature, and allowed us to glimpse the human nature in special years.

The safety zone set up by Rabe and other humanitarians in Nanjing for the Nanjing people caught in the war is like an island in the center of a storm. Under the cruel measures of the Japanese, ensuring the safety of the civilians is tantamount to seeking skin from a tiger. Rabe and others struggled to maintain the safe zone. The film does not use a lot of bloody scenes to show the brutality of the war, but it does convey a sad sense of powerlessness to the audience. Killing is aimed at a group, hypnotizing oneself is facing a group of inferior, to be conquered, the guilt of killing can be minimized. In the slaughter, one side is an inhuman, silent group; the other side is a live, concrete life, switching back and forth between the sociological individual and the biological human being. The film maximizes this interlaced display It tore the nerves of the audience, and it also highlights the dignity of life to the greatest extent.

It can be seen from the film that Gallenberger's grasp of the human nature of the Chinese is relatively accurate. The Chinese are like a group of silent and harmless lambs, but you can't deny their superior intelligence and the tremendous energy they can burst out. This is a country that can do miracles. The amazing endurance of Chinese nature often endows them with many beautiful virtues. Whether it is "a place that can hold 100,000 people, it can hold 200,000 Chinese", or the Japanese commander's understanding of the large number and extremely resilient Chinese (the wisdom and uncontrollability of the Chinese made him choose to massacre prisoners of war) , or the portrayal of small characters such as drivers, assistants, and female students in the film, which can basically be recognized by Chinese audiences and awaken their deep awareness in their cultural genes.

At the end of the film, Rabe reunites with his wife and returns to Germany. The warm farewell scene is like a fantasy in the city of Nanjing. It seems to give people hope, but it cannot make people ignore the tragic core beneath its surface information-whether it is the fate of the 200,000 Nanjing people in the protected area or the various hardships that Rabe will face after returning to China, they have not followed suit. It ends with the end of the film.

In Rabe's Diary, we can briefly step out of the victim's identity and examine this history from the sidelines. The Chinese have never been afraid to face suffering, but are often anxious about the way history is viewed. The anxiety in the process of opening the wound is often greater than the degree of pain felt, which is probably a psychological effect. "Rabe's Diary" picks up a lot of memory fragments that have been neglected for us. From this perspective, it is probably a reconstruction of historical memory by images.

View more about John Rabe reviews