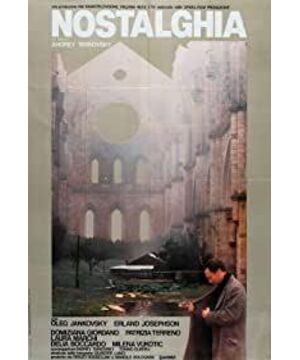

Movies are certainly not novels. Although analyzing a movie from the narrative level is the mainstream of current film reviews, even if this is the taste selected by the market. However, he still has his own unique skills and unique advantages. Andrei Tarkovsky has inherited the formalistic tradition of Soviet directors, although unlike his predecessors, such as Kurišov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, the montages, Close-up shots and thematic editing, but as a master of “creating a brand-new movie language, capturing life like reflections and dreams” (Bergman language), the movie images he presented to the audience through the camera are poetic The picturesque artistic conception is well-known. There is no doubt that such a "film poet" must be ingenious in how the camera controls and the scenes are scheduled. "Homesickness" is one of Tarkovsky's masterpieces. It presents the loneliness and melancholy of a Russian writer who went to Italy to do research. Be the protagonist Andrei After Gortchakov stayed in the hotel in the Italian town of Bagno Vignone, there was a long shot of Andrei's activities in the room, imprinting his distinctive Tasmanian style. This shot starts around the 24th minute and 20 seconds of the movie. The camera was placed at the door of the room facing the head of the bed from the beginning, without any movement, swing, or elevation. Andrei walked into the lens from the door (behind the camera), turned his back to the audience, and threw away the collection of poems by Russian poet Arseny Tarkovsky translated into Italian. In Andrei's eyes, "Poetry is not translatable like other art." This throwing action fits with the movie's theme of "homesickness", because its motivation is undoubtedly the love and defense of the mother tongue, especially in a foreign country. Time. Next, Andrei walked to the side of the room, put down his suitcase, turned off the bathroom lamp and bedside lamp, went around to the left side of the bed and opened the wooden window, walked to the edge of the bed and sat down, tilting his head and sinking into thought. There is no music, only the sound of rain rushing outside the window. This is a typical Italian weather. Such heavy rain will not fall in my hometown, Moscow. Andrei wiped off his shoes and peeled off his coat, lying on the bed with his head facing out. At this time, the camera started to move. It was a quiet and slow push of the track, but it was in the same line as the previous positioning, and there was no such indiscreet jump cut that other directors often used. At this moment, a sturdy wolfhound walked out of the originally quiet bathroom inadvertently. This runs counter to the delicateness and gentleness of Italy. It is not difficult to imagine that when Andrei dropped his right hand from the bed to caress the head of the yellow dog, he also felt it. Body temperature in the Russian countryside. When the picture gradually shrinks from the panoramic view to Andrei's head close-up, the original low-key lighting has also become a high-contrast lighting with a strong contrast between light and dark. The camera appropriately stopped at the head of the steel bed. Through the holes of various shapes cut out by the iron bars, you can see the side backlight from the left hitting Andrei’s reclining face. The whole lens, Except for Andrei's calm face and the lock of white hair on his head after falling asleep, they were all buried in dark gray and pure black shadows. Obviously, the high-contrast lighting here is different from the high-contrast lighting in "Apocalypse Now" when Marlon Brando confided to Captain Willard in the castle; it is also different from the classic "Godfather" first and second in the gangster movie. In the Ministry, the large-scale shadows created by the low-key lighting method everywhere are contrary to the intent. Andrei’s bright face is filled with a vague halo, as if the fade-in and fade-out processes that are common in movies, suggesting that the film is about to turn into the character’s dream; but the white hair on top of his head is so clear that it is stubborn. Reminded Audience, this is Italy in reality, not Russia in dreams. Tarkovsky is here, making a new interpretation of brightness and shadow. Brightness not only symbolizes light, safety, and joy, but shadows are no longer just the cloak of darkness, fear, and melancholy. In Tasman’s lens, when bright is covered with a gentle halo and is wrapped in a vast shadow that occupies an absolute dominant position, the dark becomes a strange foreign country, cold and lonely; bright symbolizes Andrei’s kindness. It is conceivable that Andrei would forget the look in his family's expectation in his dream. This shot ended around the 28th minute and 20 seconds of the movie and lasted 4 minutes. Tarkovsky's delicacy is impeccable. During the period, there was no line, no note, no second person, and no violent editing such as flashbacks and montages. It's just a long shot, just a few actions, just the movement of the camera, just the change of light, but it makes the audience quietly sad. Much better than Guo Jingming.

View more about Nostalghia reviews