I. Topographic amnesia

The planes of the beach and the sea, the façades of the cliffs, form a right angle that is too steep and too decisive. It incorporates into the process of consolidating its image of absoluteness all the glances it casts upon it, all the glances that seek to identify itself by getting feedback from it: the wind, the waves, the sand floating in the smooth low air. And dust, the foam ripples on the beach, the folds on the silent stone walls reflect the sunlight like crystals... a spatialized black hole of time.

People set up tents and parasols on the beach, trying to establish a stable coordinate system on this unfamiliar terrain that is too empty, and it is also a coordinate system of inner order - a warm family image. But the terrain has its own grammar, and it forces the camera to speak in its own language: in one of the children's grabbing games, the camera snaps out of a close-up of a boy's face, then snaps back into focus. While chasing the two girls running behind him, one of them was about to catch up with the other, the ensuing circle movement and pulling again showed an indisputable distance between the two girls, and then again, when the girl ran Xiang boy, we can't tell whether the camera that carries our eyes is catching up or pushing up. Then, more and more inhuman sights poured in: the toys of sitting adults and children were juxtaposed in a split-focus shot, the faces were frequently squeezed to the edge of the frame, leaving a lot of void in the middle, And those impossible positions—from the waves, from the middle of the skeleton, even from the heroine's cut stomach. The laws of perspective and the paradigm of scenography on which viewing relied have failed.

All things are casting their sights and participating in this grand cycle in an unprecedented acceleration of the passage of time. The audience's gaze is subject to the same degree of horror as the characters in the film in this loop: what is it that guides my "seeing"? Disaster ensues, as people rush from one side of the beach to the other, where the ubiquitous Eye of the Camera can span those distances with just a nudge. The terrain here loses the sense of security that can be grasped by sight in the geometric sense - we can't even anchor our own position, or what is the use of knowing where we are? For viewers watching a movie, it couldn't be more terrifying, and our eyes were literally thrown into the terrain.

It doesn't matter, we still have the characters we know; the characters think the same way: we still have family we know. But in the blink of an eye, the mother no longer recognizes her child. When everyone gathered in a circle to discuss countermeasures, the jagged stone walls quietly overlapped on everyone's faces. The movie made a subtle metaphor here: the face is the terrain. The same confusion and short-term amnesia that people encounter on topography occurs when people face the faces of their loved ones. "You have wrinkles," the heroine said to her husband. Before we know it, we no longer recognize the faces of the people we are familiar with, which also means that we may not recognize ourselves at this time. The coordinate system of the inner order is also destroyed. The forgetfulness of the terrain is ultimately the forgetfulness of the existence of "I".

II. Stories

What does a genre story need? It begins with a coincidence (which may later prove to be no coincidence), disaster or challenge befalls the protagonist, forcing them to act and rethink themselves in the process, the protagonist will meet all kinds of people, wise, Guides, guardians, healers, maybe betrayers, and finally, the end of the story. Banshee shows us this composition. But this composition poses a question to us, to the filmmakers: Why watch/shoot it when genre films have similar stories?

In fact, a story that always runs in the right direction and stops contentedly upon arrival is a story "told to myself", especially when it is built on the surreal. Because no matter how well-argued it is, no one really believes that a sandy beach can make people age faster. The story is not open to anyone but only persuades itself, no matter how absurd that may seem. But knowing that is of no value to the movie. Film writers are interested in situations and motion. The story merely explains the movement semantically, but denies the intensity of the mise-en-scene, but it is these sensible intensities that really constitute the situation of the film. In this sense it may be said that story is the enemy of cinema. And movies survive by tearing apart the fissures in the story that come from: the time it takes the camera to circle the crowd, the time it takes to turn from a man's back to his wrinkled face, the time it takes to stare at a couple talking to each other , as well as the deformation time extended by the terrain vertigo array deployed by the footage and montage.

Should old age, disease and death be consumed like a story? The pharmacists told the story of the epilepsy patient with excitement, and they witnessed her ending so easily, as if they had heard a thousand and one nights in one day—the only thing the story could give in paranoid self-persuasion: an ending. And the film is to fight against this uniqueness.

The way the film confronts is not to dismiss falsehoods, on the contrary, Shyamalan makes us believe the story.

III. Children

It is childlike innocence to block this slow-release agent that "story-likes" people's life experience.

To maintain innocence, Shyamalan has continuously waved this banner in his previous works. From the original "The Sixth Sense", "Omens of the Sky" to "Mysterious Village", and even "Split" in recent years, there are no protagonists. Not someone with a childlike innocence. They believe in all kinds of bizarre stories, but have little interest in the laws of the practical world.

In these works, Shyamalan uses amusement park-like sight scheduling to take us into the worlds in the eyes of children. It will avoid looking at an empty rocking chair when the hero and heroine are kissing ("Mysterious Village"), and it will also get under the table, in the cellar, and even impossible places, such as between the door and the door seal ("The mysterious village") Signs of the Sky”), it playfully overlaps with someone’s subjective point of view and then slides away without warning (“The Cataclysm”), as well as peeking out a curious head when he opens a door (“Underwater”). Banshee"). Shyamalan's cameras are naive, and it's hard to say that his shot designs and sequences can be read fully intellectually, they seem to be more of an interest in seeing: what's the difference between seeing here and seeing there? With this focal length or that focal length? The terrain is forgotten, it is disintegrated by the point of view of the film - to be precise, it is disintegrated by the child's eye, and it becomes more of an index of imagination: houses, villages, boulevards are no longer spatial containers determined in a geometric sense. , but an image and experience. On the beach in "Old Age", the camera is no longer blocked, and it wanders, pushes and pulls more recklessly, joining the chaos of image generation.

Through this experience, the story can be believed, and the film can thus open the rift and rediscover within it the power of movement and emotion that sends a ray extending to infinity on the circle that the story strives to close. , strikes each of us deeply; such an experience also prompts us to return to the imaginations that the images of things and spaces evoked in our childhood—who could have imagined that the secret weapon against story is hidden in a crossword puzzle Woolen cloth? Only children. Although good or bad, the ending will always come, but the movie has completed its escape, and we have also escaped from the natural law of birth, aging, sickness and death into the endless stretch of the dream space that the movie has opened up for us. Like that beautiful coral reef, a movie, a timeless poetic space.

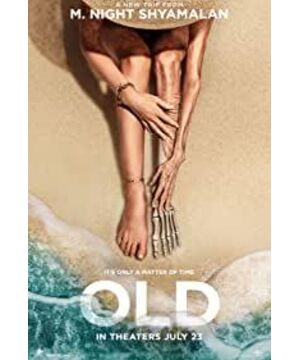

View more about Old reviews