"It may be superficial, but to what extent it is useful to think about your father's death—"

Author: Jonah Weiner

original

Years ago, after I contacted David Fincher and told him I wanted to write an article about how he made a movie, he invited me to his office to give me a personal introduction, and I could still watch it there He gets some work done. One afternoon in April, I arrived at the Art Deco Hollywood building that has long served as Finch's home base, where he was about to see footage of his 10th feature film, "Gone Girl," while post-production was underway. We went upstairs and found editor Kirk Baxter assembling a scene. Finch watched it, then asked Baxter to replay a five-second clip. It was a deceptively simple stalking shot alongside Ben Affleck as he entered a living room with violent chaos: overturned benches, shattered glass. The shot moves at the same speed as Affleck, gliding with the constant fluidity that Finch likes to do with the shot. Just three seconds later, something was wrong. "There's a bit of a wobble somewhere," he said.

No living director has surpassed Fincher's reputation for precision. Any description of his method without exception mentions how many shots he likes to take, which may annoy him, not because it's inaccurate, but because it instigates him to be seen as a dictatorial picky art Grandmaster. Finch, 58, believes that portrayal misses the point: If you want to build a world as engaging as the one he's trying to build, you need actors to push their performances into areas of uncertainty, Get rid of all traces of what he calls "performance". Then you need them to give you options while hitting the exact same markers (as did the cameraman) to make sure there are no continuity errors when you cut the scenes together. Before, say, Lens 9, getting all these stars to align is theoretically possible, but operationally unlikely. "I get it, he's a perfectionist," Finch volunteered. "No, it's just that there's a difference between mediocrity and Shang Ke."

Baxter played the sequence again, and this time I spotted a small disguise of the cameraman's hand—a blip before the camera stopped. Jeff Cronin-Weiss, the photographer for "Gone Girl" and several other Finch works, later told me that Finch was not interested in anything on screen that might pull the audience out of the "journey" he constructed. Be alert to distractions. "It can be unconscious - you can come out of a movie with 10 soft shots, which is to say they lose focus, and say, 'That's pretty good'. But David's thought process was Eliminate all of that -- try to make sure there aren't any of those mistakes." Brad Pitt, who has starred in three Fincher films, recalls that there were times when they "were a shot where there was a little unnoticeable shake." , you can see Finch really getting nervous - like, it's taking a toll on his body."

Finch put an encouraging hand on Baxter's shoulder. "It worked fine," he says. We head back to Finch's office, where a swatch of fabric hanging overhead softens the sunlight pouring in from the skylight. I didn't realize it, but Finch was at a crossroads. "Gone Girl" will be released in October, and while he co-authored Gillian Flynn's adaptation of her wildly popular thriller, the film's commercial success is not guaranteed. His last work, "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo," the lavishly terrifying $90 million adaptation of another bestseller that was meant to kick off the trilogy, premiered on holiday weekend. It came in fourth at the box office, and plans for the trilogy were shelved.

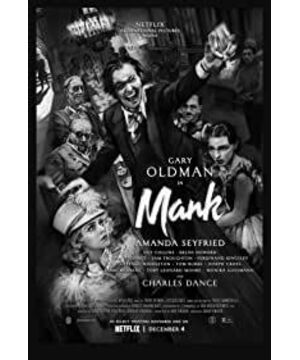

Finch has been in Hollywood long enough to be relatively comfortable with the situation: He's familiar with the industry's unpredictability, not to mention its brutality. But in recent years, studios have become increasingly hungry for blockbusters, making it less and less likely to fund the mid-budget films that Fincher excels at, such as his masterpiece Zodiac (2007) or The Social Network (2010). ). Or, there's an unfinished project, "Mank," written by Finch's journalist father, Jack, on a bookshelf in his office, among other clutter. 'Munk' tells the story of how screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz drank himself like crazy while writing 'Citizen Kane' (a landmark 1941 Orson Welles film about a loose The story of the fictional American tycoon William Randolph Hearst).

Fincher later told me that the idea for the film came about "around the time of Alien 3," his first and a notorious flop. He was the third director hired for the beleaguered production, forced to start filming before the film had an ending, and then left out of the final cut—the result was a commercial bomb, and he wasn't alone spat). In an ideal world, he said, he would have made "Knight" instead of "Alien 3," "but I had to go and cut my own throat in slow motion." Finch has held out hope for the film for years. , even if other jobs beckon and financiers have little appetite for a "movie about an old black and white movie that no one will understand".

When "Gone Girl" came out, it made a whopping $370 million at the box office -- but Fincher wasn't making movies by then, at least not yet. A 2013 test run to direct the Netflix series House of Cards inspired him to do more TV. He proposed that I anchor my profile on his planned big-budget remake of the British dark series Utopia for HBO. He also mentioned that he wanted to adapt "Mindhunter," a true-crime book about the origins of the FBI's psychoanatomy unit. The series will distill one of his long-standing thematic concerns: the tension between anarchy, violence, and perverse forces on the one hand and efforts to thwart, decode, categorize, and otherwise control this chaos — and bloodshed .

But as time went on, months turned into years, and Utopia stagnated in HBO's budget impasse, so did my articles. In 2016, Finch moved to Pittsburgh to oversee the production of Mindhunter, and when I emailed to see him there, I didn't hear back. He made two seasons — the first was good, the second was great — and then, by last year, he was ready to return to filmmaking. "It sounds ridiculous, but I didn't realize how all-encompassing doing the show was," he told me, the two of us in his office again in March. "Ninety hours a week, you're never going to improve." He explained that Netflix invited him to work on "'some little project you've always wanted to do.'" I said, 'I'm sending you this script'. I didn't tell them it was going to be a black and white movie, and I didn't tell them it was going to be a period drama. '

To his surprise, they had no objection. "I said, 'Really?'" So he invited me back to Los Angeles as he was working on his 11th feature film, "Manke."

"Mank" will resonate deeply with Americans after 2016. It is set in Hollywood at the end of the Great Depression, when Americans are impoverished and their monstrous wealth is concentrated in the hands of a ruling class determined to stifle the nascent wave of socialism (there is a "fake news" sub-scenario involving the Purton-Sinclair campaign for California governor in 1934), fascism looms here and abroad. Against this backdrop, the film tells the story of a "wonderful great writer," who, as Finch describes Mankiewicz, "whom Orson Welles gave him the cover to expel about the rich. and the gall of the poor, and about Willie Hirst's bizarre lack of empathy for the poor".

Finch shot the film in and around Los Angeles, starring Gary Oldman, who had been editing for three and a half weeks at the time of my visit. "We were six days over - so that's what we had to do overtime," he said. There was less frustration in his tone and more acceptance with a shrug of his shoulders, a calm that stood in stark contrast to the world beyond the walls of his office. Just a day earlier, panic was mounting as the spreading coronavirus forced the NBA to suspend its season. Every once in a while, Finch reads news updates aloud from his iPad, but most of the time he concentrates on Mank-related work. (Finch staff will start working remotely or staggered shifts over the next week)

For Finch, the meaning of "Mank" is multi-layered. First, Finch advocates "citizen Kane". "I don't think it's the greatest American movie of all time," he said, "but it's the top three -- and they made it in 1941." ("The Godfather Part II" and "Maybe 'Chinatown'") On the other hand, Jack Finch - his father - David called him "the most important writer of my life, not only the first person who introduced me to Citizen Kane, but the first The man who introduced me to the movie" - died of pancreatic cancer in 2003, script in eighth draft.

"When Jack retired," Finch continued, "he said, I really wanted to write a script." Finch encouraged him to reread Pauline Kyle's 1971 tribute to Mankiewicz, "Bringing Up Kane." : "I said, did Mankiewicz have a movie that pulled this thing out of the ether and put it in front of this movie kid for him to shoot? Jack went and wrote the script, which was really good." He said, the only What needs to be revised is that his father "never understood the inherent cynicism of Hollywood - he did not understand Hollywood's magnetic pull on sociopaths".

Finch has a hilarious sense of humor. You can read his fondness for a wit like Mankiewicz in his own scrimmage, expressed in a playful spirit of sport. At one point, we were watching old movie trailers together—he was going to use them as a template for Mank's promotional material—and we watched the Gone Lover trailer, during which Finch said, "It's just A soap opera." It's just a soap opera, isn't it? "

He was wearing a white T-shirt under a grey cardigan, and among the items neatly arranged on his grey-stained wooden desk were eight pairs of glasses, a gold Apple Watch from Jony Ive, a pack of promises "Privacy" black glued webcam cover, and a notepad (another gift) with DAVID FINCHER in block letters at the top of each page. As he spoke, his fingers wiped and smeared across the surface in front of him, clearing particles of real and imagined without graffiti in an absent-minded exercise. "I think he's obsessive, in a way," screenwriter Eric Ross, Finch's friend and collaborator for years, told me later. "I love sitting at his desk and fiddling with all his footage, watching him wipe the condensation off the can of Diet Coke I just drank."

After a while, Finch went to a small screening room, where we met Eric Weidt, the colorist on "Mank," who balanced it in black, white, and grayscale until Finch was satisfied. Finch said the general idea when creating the look and sound of the film was: "What would the film look like if it was shot at the same time as Citizen Kane?" "If Welles and the Does the movie matter?" The camera angle is low and the focus is deep. The footage — shot with a monochrome sensor, which Fincher first asked digital camera company RED to develop specifically for him in 2012 — would be processed to look like old film. Finch's longtime sound designer, Ren Klyce, will oversee a team of technicians as they analyze the audio spectrum of films of the era and—in an elaborate process that includes "re-recording the final mix in theaters," To make it feel more like an old theater sound", as Fincher's production partner and wife Ceán Chaffin put it - trying to make Mank sound like them too.

Finch likes to fiddle with everything we see and hear in his films, finding new digital technologies in every project that he fiddles with on a finer and finer scale. For Mank, he fumbled through the scene frame by frame each time—painting clouds into the open sky, multiplying roadside dust by passing cars, and adjusting the brightness of the background streetlights to not Giving off that distinct (to him, if not to me) sheen of a "modern metal light fixture". Knowing that he had so much editing power waiting for him gave Fincher a lot more slack on the set than before. He refers to a scene at the end of "Mank" where Amanda Seyfried's wig (she plays Marion Davis, the movie star and Hearst's romantic partner) is shedding hair. He recalled that Seyfried's hair "was right in front of her eyes, and they wanted to cut it and run in. I said, 'She's got us something great.' So what about those hairs?" "I can cut them later. Get it off, trust me."

One of the most remarkable techniques Finch helped pioneer was called lens stabilization. Starting with The Social Network, he shot 20% larger than needed for the final shot. This created a redundant buffer of visual information that allowed him to digitally correct for the slightest judder, bump, and sluggishness, removing all imperfections from camera movement. His shots represent a sort of impossible—and faintly malicious—the gliding, unadorned stare of the eye. "I want it to feel omniscient," Finch said.

Stabilization also allowed Finch and his editors to rescale entire shots after the fact and build seamless split-screen composites that stitch different shots into one. For a direct example of Finch's stabilized footage, you can watch the "Red Ribbon" trailer for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and notice the ominous, tractor-esque smoothness of the footage as it is pulled toward the Van Yell mansion. But it's the effect Finch deploys on seemingly inconsequential material, like a character laying a drink on a table, and every shot he takes in "Mank" ends up stabilizing -- which he calls the The movie "is as labor-intensive as any Marvel movie on a pixel-by-pixel basis." Chaffin described his rigor in "Mank" with a kindly point of view. "David is a freak," she said. "He checks every frame."

The basic formal joy of watching a Fincher movie is that every last-micron experience has been considered and then rethought, with love, finesse, and precision. Sitting next to Weidt, Finch scans "Mank" for elements that excite him ("I like the little light under his ear hair") or irritate him. When Finch complained about a pit player's collar being too bright, I said his eyes were traveling to details that the audience would likely never notice. "Hopefully!" Finch said, adding. "We're trying to control where people's eyes are going, so they don't end up looking at things that just confuse them. That's the simplest description of a director's job: 'How can I get them to see where I need to be?'"

In films such as "Fight Club" and "Cry Room," Finch is sometimes associated with a flashy, nonchalant style for which he used special effects to have his camera fly into the wires of the refrigerator and through the handle of the coffee maker. But Mindhunter and Mank cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt emphasizes that since Zodiac, Finch has been leaning towards a "very classic" visual rule whose rationale predates the French New Wave and Aestheticism . Finch tends to avoid hand-held shots, except on rare occasions where his camera usually only moves when the actor is moving — and at the same speed. Cronenweth told me, "In most feature films," Finch's rule is that if the actor "slides forward a little, we slide with them. They adjust, we adjust. They stop, we stop." Come down. David is very clever with designing the movement to enhance the scene - not for movement's sake, but for more intimacy with the characters."

Brad Pitt, who called Finch "one of the funniest [expletive] people I've ever met," and who regularly gets together with Finch on movie nights, said: "During this period, he's been Muttering: 'This shot works. It's a bad transition. Why are you going to get in that glove? Hold on!'. It's like watching a football game with Bill Belichick." Finch described playing as his favorite The video game Madden NFL is "the only time I don't think about movies"). Another good friend, filmmaker Steven Soderbergh, told me he visited Fincher during post-production on the 2002 thriller "Thriller Room." Soderbergh described the scene this way. "David took out a laser pointer and he circled a wall in the upper part of the frame and said, 'That's too bright, it's a quarter aperture. "I had to get out of the room. I had to get out of the room. I had to go outside and take a deep breath because I thought, oh my god -- see this? All the time? All the time? Everywhere? I It can't be done."

When I asked Soderbergh to name his favorite Fincher movie, he replied that it was difficult to choose one, but if you rank it by the one he rewatched the most, it would be "Thriller Room." This is an uncommon choice. The film — Jodie Foster fending off a home intruder one night — is a formal exercise in spring and rain, set almost entirely in one location, and it offers no overarching view of human nature, or knowable Limits, or the extreme ambitions of a sociopath, as Fincher's other films have done. However, Soderbergh believes. "I don't know who else could imagine executing something like this and have the perseverance to do it. It gave me a headache."

Soderbergh is careful to praise more of Fincher's formal dexterity: "I think because people are blinded by his extraordinary visual dexterity, he doesn't get enough credit for his understanding of the story." Several collaborators have emphasized this point. Eric Roth, who wrote Fincher's "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button" and helped finalize the script for "Mank," told me that Fincher was "more than Learn more about the narrative and the purpose of things in the script". Andrew Kevin Walker, the screenwriter of "The Seven Deadly Sins," Finch's shockingly dark serial killer blockbuster, and who has also done pro bono work for Finch's other films, said: "If David wants to take the time and he can write his own movies."

In a discussion about screenwriting, Finch said, "It's not really a screenwriter's talent to come up with a good line. The talent is, when do you say it?" And, he added, "Strategic silence can be just as inspiring. Stunning." Actor Holt McCallany, who co-starred FBI agent Bill Tench in Mindhunter, retells a compelling anecdote that illustrates the point. In the second season of the series, Tench has learned that while he is hunting a serial killer in the wild, his underage son is involved in a heinous crime at home. The child stopped talking, his behaviour continued to be erratic and Tench's family life was under severe stress. "My marriage is falling apart, and in this scene, I'm trying to communicate with my little boy at the ice cream parlor," McCallany said. "During the rehearsal, David said, 'This is the moment it hits you.' That's how it will be from now on. It won't change'. "

Such a bleak explanation "wasn't I thought of," McCartney said. Finch succeeds in illuminating the show's driving theme with one note: the mutability of authority, the folly of trying to build a bulwark against the inexplicable. "That's what it means to be in the presence of a great director," McCallney said. "Because what he said was not in the lines."

On his desk, next to the keyboard, Finch has a black-and-white photo of Jack at rest—on the sofa, hands clasped, eyes closed. This is a photo Finch took in 1976, when he was only 14 years old. "That's why it's out of focus," he told me. Finch was born in Denver, but when he was young, his parents moved to Marin County, north of San Francisco, where Jack wrote for Life and other magazines, and his wife, Claire, was part of a company called Marin Open. The Mental Health Nurse at the Drug Rehabilitation Center at the House” (which happened to be where she worked for Charles Manson’s former parole officer, Roger Smith, an important figure in Manson’s counter-history who would become Finch family acquaintances). Finch has two younger sisters, one of whom, Emily, unknowingly instigates him into a prank that predicts his future interest in horror acting. He once stole baby dolls from her room, wrapped them in "hamburgers and ketchup" and then "threw them on the highway," he recalled in an article in "Interview," for drivers to see the baby on the asphalt The scene of the explosion.

Finch once described the shockingly popular psychoanalytical atmosphere of Northern California in the 1970s—a time and place he vividly recalls in "Zodiac," a film about the time when Finch was a kid in the Bay Area. Restless real serial killer - an atmosphere of "overindulgence". "It was all too much, 'What do you mean?' 'Let's dig a little deeper on this,'" he once recalled. He noted that he had "a handful of friends who were from Marin County at the same time, the same age." Duan, they're all very insidious, dark, funny people." Perhaps, he added, "Zodiac" — an epoch-making horror that hits a seemingly idyllic place — "has something to do with it."

The Bay Area is also a hotbed of filmmaking. "Shady Lane was closed so Coppola could shoot 'The Godfather,'" Finch said. "Our next-door neighbor is George Lucas." (The director bought a grand Victorian building in this otherwise humble neighborhood.) More than any of these influences, though, was Jack who inspired his son's passion for the film. love. As a child, Jack "had a horrible, abusive relationship with his father," Finch told me. "He's a violent alcoholic, so Jack counts as the babysitter for the movie and gives him 15 cents and is expected to disappear from noon to 6 on Saturday. He's in love, and he gave me that love very early on." Something You must watch" Fincher recalls watching '2001: A Space Odyssey' and 'Yellow Submarine' when he was 7 years old. "It's one of my earliest cinematic memories. "

Like Robert Graysmith, the amateur detective protagonist in Zodiac, Jack was a former cartoonist, as was Finch's "favorite director growing up," George Roy Hill, who filmed Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid". "There's a sense of simplicity when you can only tell your story in three paintings," says Finch. He draws comics himself and flips through shot patterns in Jack's Hitchcock/Truvert. In high school, he moved to Ashland, Oregon, where Finch directed plays, worked as a projectionist at a second-rate theater, and worked part-time on the production side of a local TV news station. In his teens, he decided to give up college and return to working in visual effects at Industrial Light & Magic in Northern California, earning credits on "Return of the Jedi" and "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom." It was a productive decryption experience. The people behind "Star Wars" aren't gods, but their fellow Bay Area folks, groping through trial and error.

Whereas many would-be directors of the previous generation used B-movies as a springboard, Fincher honed his skills in commercials and music videos. At the age of 20, he directed his first commercial for the American Cancer Society. At the end of "2001", his footage shows a morbid image of a fetus smoking a cigarette in the womb. The industry has taken notice. Finch moved to Los Angeles to become the founder of Propaganda, an influential production company, and through his work for pop culture giants like Nike and Madonna, helped define the fashionable and hilarious visual language of the era. Among other MTV milestones, he directed the music videos for Madonna's "Vogue" and George Michael's "Freedom '90").

The young Finch drove a 1989 Porsche 911 to meetings — a gift he said was given to him after the success of the music video — with a sort of polarizing confidence. Brad Pitt told me that after his first meeting with Fincher to discuss "The Seven Deadly Sins," he "felt such a relief, awe and a renewed love for the film." By contrast, Hollywood producer and Propaganda founder Steve Golin told Entertainment Weekly in 1997: "In the beginning, David was so arrogant it was unreal. He There's still little patience for people who aren't as smart as him, which is a lot of people." To the same reporter, Finch made it clear. "A director needs to be strong. The work you do now will be written on your tombstone."

In mid-April, work on Mank was fully remote, and I was on a Zoom call with Finch and Nine Inch Nail's Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, who worked together for The Social Network. Fincher has written the soundtrack for every film since then. He didn't give the pair any specific assignments, and the composers mentioned were "various," as he said, like Bernard Herrmann and Ryuichi Sakamoto, who delivered for the times Temporary music written for the instrument.

Fincher's responses to these musical cues interweave questions of character and narrative in surprising ways. We saw an early scene where Mankiewicz's wife, Sara, helped him to bed, fully dressed and completely slushy. "I love that little thing you have here," Finch said, "because it doesn't sound sad - it sounds cute. Mankiewicz is sad enough. The music is about their honeymoon or courtship is What it's like, not what we're seeing now, this guy can't stay overnight without being absolutely bombed and she's cleaning up after him."

Finch formulates his notes as demands, not as demands, but more as evocative abstractions. "The music is a waterfall, and it's turned into mist here...." By the end of the call, things turned into a logistical issue: How would the composers record an orchestra given social distancing? "We're going to look for creative ways to make it happen," Reznor said. At this event, musicians will be recorded in isolation and then woven into a virtual ensemble.

A few weeks later, Finch had another video call, this time with actor Tom Pelfrey, who played Mankiewicz's buddy Joe. In a recording studio in New York, Pelphrey performed an automatic dialogue replacement, or ADR, the process by which an actor re-records lines because of technical problems with the original sound or problems with the original performance.

Finch paid particular attention to a scene in the Paramount Screenwriters Room in which Joe spoke to the stenographer on and off. Wait a minute, if... give me a moment, right down there... oh, we already have this... okay, okay, let's move on...

Perfrey tried it. "Fine," Finch said. "Your chin is down, your throat stops a bit, give me a little more protruding." Perfrey tried again. Then tried again. "Good," Finch said, and then offered a note about Joe's state of mind. "When you get to 'Damn Studio Pagination,' that's your industry of choice. You hate that you have to deal with it. But in the Great Depression, $750 a week." Perfrey nodded, It took a few more tries, nine in total - during which time it was discovered that the dialogue was barely audible in the final mix, and the scene with Joe on the sidelines had nothing to do with him.

In Zodiac, for the set in the San Francisco Chronicle, Finch instructed his prop master to print a front-to-back replica of the newspaper—accurate to the page, accurate to what was depicted in certain close-ups Days - even though these things are only glimpses on the screen. It occurred to me that I had just witnessed the sound of the Finch-caliber set dressing up. "It's going to be subtle," Finch told Perfrey. "You're just giving us the feeling that geniuses are messing around."

Some collaborators were thrilled with Finch's carefulness. Rashida-Jones told me that on "The Social Network," Fincher broke a "bad habit" she'd developed by carrying a set of "techniques that I know 'works'" - a buildup of past acting experience instinctive performance. "I think I've got through a shot before David takes me aside and finds every trick and lets me get it done." Amanda Seyfried framed Finch's repeats Compare it to working in a theater, where an actor discovers something new in the same material day in and day out. Finch's set "felt more like that than anything else I've ever done," she said. Rooney Mara, who starred in "The Social Network" and starred in "Dragon Tattoo," said, "There are many times when I want to do things differently, or I have my own ideas that things should be like this, He's not conceited if it's a better idea," but "generally, people don't have a better idea than him."

Eric Roth complimented Finch for several minutes before saying, "Okay, let's talk about what he is [expletive]. He's a wrong-doer and he'll argue with you to the death. He's a prosecutor—he makes me uncomfortable. 'Why do you write that? Why do you think it makes sense? Finally, I said, 'Answer!'" Finch's way of doing things makes people Unhappy, Ross added, "but he's loyal, he's in his prime, he's going to have your back, he knows what he wants — an incredible thing in Hollywood."

Finch's set can get tense. He has admitted that on "Thriller Room" — where he designed every shot of the film with pre-visualization software before stepping onto the set — photographer Darius Khondji was reduced to a "light jockey." Khondji dropped out of the production halfway through. Zodiac" star Jake Gyllenhaal told the newspaper in 2007 that Finch "painted with people" and called it "difficult."

When I asked Fincher what the rumoured unhappiness with Gyllenhaal in that film was about, he described an "extremely simple" situation. "Jake is in an awkward position because he's young, there's a lot of people competing for his attention, and at the same time, the person he's working with doesn't allow you to take a day off. I believe you have to keep everything out of your peripheral vision." But I think Jack's philosophy is -- let's just say he's made a bunch of movies, since he was a child star, but I don't think he's ever been asked to focus on the minutiae, I think he's very distracted. He's got a lot of stealing Whispering, saying that "Jarhead" -- the 2005 war film starring Gyllenhaal -- "will be a blockbuster, take him to another level, and every weekend he's drawn to the Santa Barbara Film Festival, Palm Springs Film Festival and [Expletive] Catalina Film Festival. And when he got back to work, his attention was very distracted. "He's got" his manager and his stupid agent, they all come to his trailer at lunch to talk to him about the GQ cover, talk about this and that. "Finch said," he was arranged by these people, and not at the mercy of very smart people. There are too many distractions for him. "

By the end of production, the tensions had mostly dissipated, and Gyllenhaal has since apologized — "not that I need to apologize," Finch said. (I contacted Gyllenhaal to request an interview, but a rep let me know that the actor "passed on in good faith" my request). Finch added: "I don't want to make excuses for my actions. If I see someone slacking off, I'll definitely have a time to stand up. People always go through tough times, and so do I. So I try to use empathy. Go look at it. But every filming day is a huge investment, and we probably won't get a chance to come back and do it again."

He said his basic point. "I tell the actors all the time. "I'm not going to be because of your hangover, I'm not going to be because your dog died, and I'm not going to be because you just fired your agent or your agent just fired you, "he said. "Once you're here, the only thing I care about is, did we tell the story well? "

In September, I drove to Marin County to see "Mank" in the theater at George Lucas' Skywalker Ranch, where Finch spent three weeks at the mixing facility. I wasn't allowed to join him because of Covid-19 regulations, and when I suggested we meet nearby for a walk in his childhood neighborhood, Finch dismissed the idea as "too twisty." I sat down in the theater alone, and given my odd luck, I'm the only one who's going to see Mank this way - it's streaming on Netflix starting December 4th , but Covid-19 has significantly disrupted its theatrical release plans.

When I came out of the theater, the sky was dyed orange by the raging California wildfires. A few hours later, my phone was buzzing with a message. "How's it going?" "It's Finch" I replied that I liked it and we'll talk in person. Next Monday, I head to Los Angeles to see Finch again. We sat at a picnic table in the back of his office, where he followed up on his text messages. What do I think of Hearst? Was the movie unfair to him? What do I think of the last scene with Mank and Davis? How about the script - does it feel like a patchwork of scenes or cohesion? Finch was eager to hear what other people thought, he explained, because "I've probably watched this movie all the way 120 times."

I used to find Mank bittersweet and unexpectedly moving. It's a compassionate portrait of an artist in the throes of a creative crisis (Am I content to make phone calls?), turned into a moral crisis (given what I've seen firsthand how the rich exploit the poor, if I don't stand On the one hand, am I complicit?). This story of the rise of a self-destructive man, however stagnant, snuggles up in and out of Fincher's work in convincing ways. He often pits the agents of anarchy and turmoil (serial killers, tech "disruptors") against the agents of system control (law enforcement, the president), and you can see Mank in that light -- only in Here, representing the forces of turmoil in the future, is the bomb-throwing hero screenwriter who delivers the best possible attack on Hearst and the brutal hegemony he embodies.

While the script is sympathetic to Mankiewicz in this showdown, it's not triumphant. 'Manke' raises difficult questions about art's ultimate ability to change society: Hirst effectively smashes Wells' film after the film's release, even as 'Kane' is slapped with grievances for his unjust portrayal of Hearst Become a legend, but it never posed a real threat to his power. Likewise, the film might surprise those who were expecting something more gross from Finch, who generally prefers the rough to the sharp, with the exception of "Benjamin Button." With that in mind, I brought up a mystery that Steven Soderbergh posed when he was discussing Finch with me. "Draw a line from 'The Seven Deadly' and say, the same guy doing a two-hour character study, a writer wrestling with the fact that his talent has been betrayed? Those are two different universes." Of course, Jack Finch passed away in 2003. Before that, Finch had said that he "never really experienced what it was like to be with someone when they took their last breath" for the death depicted in his film. That experience clearly inspired "Benjamin Button," a fantastical film about how we and our loved ones go back and forth on our way to the grave. Zodiac also has obvious autobiographical elements. Citing this seeming change in Finch's "emotional relationship to the story" after 2003, I said: "It may be superficial, but to what extent it is useful to think about your father's death—"

"I think it's superficial," Finch interjected. He admits that Jack doesn't really care much about movies like The Seven Deadly Sins (at the beginning) and Fight Club (nothing at all), but emphasizes, "I'm not doing this for anyone. I'm going to mine. Where curiosity takes me". Curiosity naturally shifts with age, and, he reminded me, he originally wanted to make Mank in the early '90s. He suggests seeing how advances in technology allow him to tell bigger stories, like "Buttons," about a man who reverses aging, more productively. "I now have the ability to think 'what do you want to do' instead of 'what can you do'"

In addition, there are market problems. "A lot of your early work was about feeding people," Finch said. "There's a part of you who just wants to have a door panel on the door to feed the people you love and the people you work with -- at a certain point, that's not a problem anymore."

We put on masks and entered the house, and Finch showed me a trailer for the upcoming Mank. He cleverly matched it with the aria from the fictional opera "Salambeau" from "Citizen Kane." With Mank nearing completion, I asked him if he was already thinking about his next project. "No," Finch replied. "I don't have anything, I'm going, 'Oh God, why don't you just photograph it?'" He pointed to his bookshelf. "It's an interesting thing," he said. "'Munk' has been on that top shelf for so long - it's clean now."

View more about Mank reviews