By Geoffrey O'Brien/Criterion (August 17, 2021)

Proofreading: Qin Tian

The translation was first published in "Iris"

For me, it's always been a somewhat eerie hollow time: not only a formative cinematic experience, but also a sense of shock when the line between screen and life disappears. In a dimly lit karaoke hall in Tokyo, a pianist played a clattering boogie-woogie to the sound of firecrackers and invited guests to order songs. A drunken old man in a coat and a new bowler hat hummed the beginning of the song in a low voice. The pianist agrees with a gleeful look on his face—"that nineteenth-century love song?" Then takes another gulp of beer and plays a slow waltz that sounds like it's accompanying a silent movie. Old tune. (We've briefly heard the melody before the title, but its fragile, lyrical aftertaste is barely worthy of the film's opening shot: an x-ray of a cancerous stomach tumor, played by a man with a dry, uninspired voice. Emotional voice-over introduction.)

Through a curtain of beads, you can see couples walking towards the dance floor, while the old man outside the screen begins to sing in a low voice from the depths of untouchable regret: "Life is too short; fall in love, girl, in you. Before those safflower-like lips faded..." The lovers stopped and turned in the direction of the voice. The karaoke dancer, who was frivolously curled up on the old man's knee, slowly got up and exited the screen. The pianist looked at him suspiciously as he continued the mechanical accompaniment. The old man continued to sing. As he begins the second and final segment, the camera keeps staring at his face. With tears in his eyes, he looked straight ahead. For a while, everything else seemed to cease to exist.

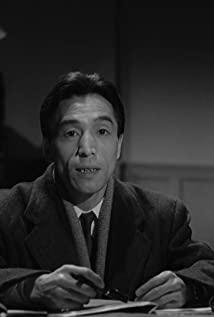

At this point, Akira Kurosawa's "Desire for Life" (1952) begins about 45 minutes. During this period, there was not a single pause. We already know this old man, Kanji Watanabe, the chief of the public affairs section, and the film effectively introduces us to the red tape of the bureaucracy he lives in, a system designed to frustrate the needs of ordinary citizens—such as A group of impoverished women try to reclaim a toxically polluted urban wasteland and turn it into a children's playground. The narrator begins by telling us that Watanabe will only have a few months to live, and he soon learns the bad news himself. In the character of Watanabe, Shimura Takashi is portrayed as a man who has cowered to the point of non-existence—he shrugs his shoulders, his eyes are always down—he can barely speak when he learns about his condition. As he walks home from the clinic, the soundtrack quiets down until he steps off the curb and the cacophony of traffic noise begins to roar again.

In the face of his son and daughter-in-law, who are primarily concerned with pension fund assets, he has nothing to say. Music added to the sense of isolation: as he hung up his clothes, tidied up his futon, and took off his watch in an unconscious motion, music came from across the room, his daughter-in-law listening to the American pop singer Tony Arden's hit single - "Too Young". He looked at the photo of his deceased wife, then buried himself in the quilt and sobbed.

Started drinking from Watanabe, an abstainer, and met a long-faced, bombastic novelist in a bar who claimed to have found something Christlike in his terminal illness and volunteered to be a Mephistopheles , guides Watanabe to experience Tokyo nightlife like he's never experienced before. The journey is both auditory and visual. In the pinball hall, we would hear the background cacophony, the clanking of pachinko discs, the busy electronic beeps. The roar of the cafe was further amplified by the harsh trombone, which confused Watanabe. As he and his guide make their way through the bustling streets, the ever-changing angles and perspectives match the musical segments, each shifting and overlapping. In a secret bar where they stopped briefly, another foreign record — Josephine Baker's "I Have Two Favorites" (J'ai deux amours) — signaled an echoing pause.

It was a break from the unbearable silence, and culminated in the chaotic cabaret performances in the karaoke hall—boozed and smoky as one dancer performed an energetic jazz dance while Watanabe staggered after her Behind, trying to get back the bowler hat she snatched away. He didn't seem to notice, and she leaned frivolously against his sluggish body. But when the pianist sent out an invitation to order a song, he didn't hesitate at all. Singing the song was the calmest move he could do when he heard the bad news.

The song he ordered was "The Gondola Song" (introduced in English subtitles as "Life Is Brief"), an exotic song from another era Ballad, composed in 1915 for the stage version of Turgenev's novel The Eve. The lyrics, which convey the idea of fleeting beauty and living in the moment, were written by tanka poet Isamu Yoshii. The song, one of the early hits of prolific composer Nakayama Shinpei, is considered a fusion of Japanese and Western pop music in a mash-up style. The song has a peculiarly tragic mood and was written for Sumako Matsui, the actress who rocked the Japanese theater scene with her performance in Ibsen's "A Doll's House", and her collaboration with the innovative stage The drama director Shimamura's ambiguous relationship has been criticized - Shimamura died suddenly of the Spanish flu in 1918, and soon, Matsui also committed suicide. (Kinyo Tanaka played her in Kenji Mizoguchi's "Actress Sumako Love" in 1947.) For Watanabe, it was an echo of his younger days—the Taisho era (1912-1926), full of New possibilities and an aura of freedom—before the Great Depression, before the war, before the American occupation.

The choice of the old song made the pianist happy, but the atmosphere soon changed as Watanabe began to sing. Akira Kurosawa wanted an effect of "getting out of the mundane", and Takashi Shimura, who had starred in the 1939 musical "The Battle of Mandarin Duck Songs," summoned a voice from the depths of his heart. He established a zone of silence where his devastating grief, the feeling of losing a life he never really lived, could finally be acknowledged. However, when he sings, he seems to be completely alive as long as he can keep on singing. As if he had found a ritualistic way to connect with the unseen, all other traffic noise, raucous crowds, and imported music were expelled beyond his singing. The song is a precarious stopover between the world Watanabe is leaving and the unknown absence it points to—"there is no tomorrow." His singing was pointed completely inward and clearly audible. Other customers were stunned and speechless, or stepped back in awe or unease, as if under a spell.

It was only a moment after all. All of this is just the prelude to a story that hasn't even begun, even though it's nearly halfway through. After this solemn pause—his voice was now a more hoarse, drunken babble—Watanabe would be pulled out by his fellow novelist, and then this Walpurgisnacht ), interrupted by tambourines at the strip club, where a well-dressed Latin ensemble played congas and brass, and the hall was packed with a smoky crowd of dancers. The two eventually stop in an alley and vomit, and the two girls they accosted in the ballroom are waiting in the taxi, trying to cheer themselves up ("Let's sing, I hate the blues"), so they sing another song. An American song: "Come On-a My House" by Rosemary Clooney.

And the story itself — Watanabe's awakening on his path to self-redemption, his battle with bureaucracy to build a children's park — remains to be told. But it will be told indirectly after the fact, through fragmented flashbacks when he wakes up, through the recollections of the most confused and unreliable colleagues and family members (not to mention drunkenness, lying, self-promotion and self-pity). )filter. We got as close to who he was as possible through Watanabe's voice, and the melody of "Song of the Gondola." Only through this song can we get the impression that we were briefly in his place, sharing an intimate space with someone whose life was so closed. Inevitably, the last time we see him, we will be reminded of the song he sang on the swings in the children's park, and with the accompaniment of the ethereal harp, he sings more calmly: his own peaceful life and death tone.

Original link:

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7501-to-the-tune-of-mortality-the-gondola-song-in-ikiru

View more about Ikiru reviews