First, the movie is a love poem. Poetry becomes a character in the narrative, connecting the postman with Neruda, with the lovers, with the world. The audience follows the protagonist into a poetic point of view, thus immersing themselves in this soft, romantic yet rough, real world. In addition, the protagonist sends letters again and again seems to become the rhythm of the film, making the film a modern poem that begins and turns, from the beginning of separation, to gradual understanding, to becoming a confidant, and finally lost in the vast sea.

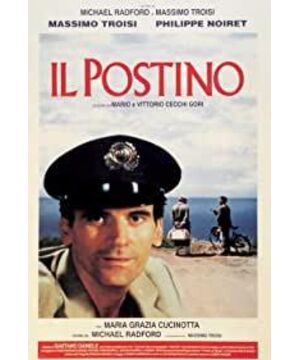

Second, this is a love poem written for the movie. Offscreen, I learned that Massimo Trossi, the film's director and postman actor, died of a heart attack shortly after the film was completed, and he didn't have time to see what he had devoted his life to. Before his death, the actor was already the most successful comedy star in Italy. He insisted on completing the film despite being short of funds and seriously ill. This story and the film itself form an intertextuality, and the love for the film becomes immortal in the form of images. Although in the world of film, business has always controlled the discourse, it is this love of film over the past hundred years that still has a unique charm.

Finally, this is a love poem for the twentieth century. Filmed at the end of the twentieth century, the film is like a look back at history. On the one hand, the film uses poems, letters, bicycles, tape recorders and other media to convey emotions, and it reproduces the nostalgia for the past, which is reminiscent of the old light and shadow space in "Cinema Paradise". On the other hand, the film inherits Italian neorealism, recreating those stories that have been submerged in mainstream discourse. It records the ideals and beliefs of communists in the last century, and it tells the admirable backs of little people in the torrent of history.

View more about The Postman reviews