TRISTANA, Buñuel's uncompromisingly acidulous and formally decorous moral allegory, has deceptively bare-bones plot, in the wake of her bereavement, our titular 19-year-old heroine (Deneuve) moves into the household of her new ward, Don Lope (Rey) , an erstwhile suitor of her deceased mother, who is reputed to be impeccable in personality and moral standing, but hinted by his maid Saturna (Gaos, a diligent servant who is equally diligent in keeping her own counsel albeit being in the know throughout), he has a particular soft spot for woman.

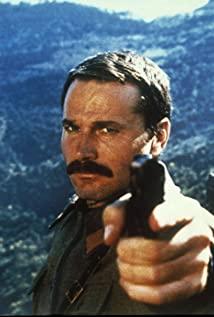

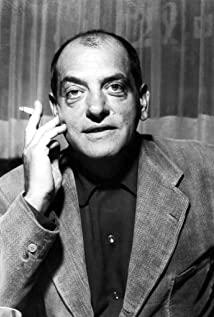

Descending from gentry stratification, Don Lope is not rolling in money, whose atheistic, socialistic belief also falls foul of his own family members, a hardened bachelor, he is not sated to be only a father figure to a nymphet like Tristana, but also her husband, which a docile Tristana complies under his paternalistic persuasion, but instilled by Don Lope's self-contradicted “talk the talk and walk the walk” ideologue (one must free to love, but as his nominal wife, Tristana cannot do anything to spoil his name), a susceptible Tristana, who has an idiosyncratic preference over even selfsame things (pillars in the church or two chickpeas), gets tired of this cradle-snatcher and gets her feet wet in the outside world, and soon, falls in love with a visiting painter Horacio (a four-square Nero),who will spirit Tristana away from the town of Toledo, there is nothing Don Lope can do to obviate it.

Several years later, the tidings that Tristana is back in Toledo with Horacio, jolts a salt-and-pepper but newly inheritance-received Don Lope out of placidity and he magnanimously grants her wish to stay with her “father” for her malady, a tumor grown in her leg, and before soon Horacio is driven out of the picture, everything seems to return to the status quo, with Tristana now an embittered amputee, and Don Lope eventually gets her acquiescence of matrimony (her wedding dressing is exactly the same color of her mourning in the beginning of the story), but their union is deficient in domestic bliss, even when Don Lope becomes more tolerant of Tristana's emotional distantiation, as foreshadowed by Tristana's horrific nightmare in the belfry (the only surrealistic masterstroke Buñuel flourishes in the film),the precognition will become true in a deadly winter night, when Tristana finally turns the tables on her scorned husband, after a sequence of rewinding montages, the film brings down its curtain.

Much more than a cautionary tale about a middle-aged prig's inveterate nympholepsy, betraying by the title, the film puts its heroine in the dead center, Tristana's metamorphosis is something so staggering that the whole innocence-eroding-and-acrimony-crystallizing process cuts like a sharp-edged knife to anyone who can claim enough faith in humanity, and we can see where the canker lies in the opposite sex.

Deneuve is at her most impressive when her brazens out Tristana's ruthlessness after being physically punished for her right to love, the unflinching gaze she projects upon Saturno (Fernández), the mute son of Saturna, when she bares it all, is soul-shatteringly chilling and disdainful, it constitutes a transcendent moment when emancipated female body squashes the lascivious male gaze from the ground up. Rey, on the other hand, imparts a fully sympathetic persona despite Lope's unsavory disposition, a typical product of a patriarchal society who abuses his entitlement , swallows his pride and dissipates his fortunes, Buñuel is ever so sharp-eyed to pinpoint our species' inherent frailties and show us the consequences in such explicit minutiae, TRIISTANA is here to stay.

referential entries: Buñuel's VIRIDIANA (1961, 8.2/10); EL (1953, 7.6/10); BELLE DU JOUR (1967, 7.9/10).

View more about Tristana reviews