foreword

Perhaps it is possible to categorize films in this way, two kinds of space, clear or turbid. It is first and foremost a perceptual definition of film space, derived from intuition rather than the presupposition of what is the basic unit of film. Is it possible that one shot is cloudy and the next is clear? Or, this one is muddy, will the next one change? These questions reflect the entanglement of general opinion and specific practice, and since each individual film has its own thinking about concepts such as "shot" and "field", it is impossible to answer such questions. . We might borrow the usual montage school saying that meaning always arises at connections. And "clear" or "turbid" is a certain meaning expression of space.

It is easy to make some judgments, for example, Roy Anderson's films are obviously very "clear", while most of Pasolini's films seem to be more "turbid". More movies find their niche in between. Of course, we also have to face some tangled moments. When some films or authors are questioned twice, their positions sometimes change in leaps and bounds. For example, Hong Changxiu, his seemingly clear and lively "skimming" films, I think they should also belong to the "turbid" side. Or, is the push-pull lens itself "turbid"? And a fixed lens must provide some kind of "clearness"? This sudden change in judgment seems to undermine the explanatory power of such a categorization itself, but it is also a kind of truth about how the world works, as when people change their political stance, there is no slow process.

The first is the "clear" movie, which requires the creator to have a "cleaning" ability. That's why almost the entire Soviet school of montage is "clear". Extreme "clearness" is a dead silence, a world of inorganic matter, which includes the derogation of people. In this sense, Buñuel's final trilogy, seemingly chaotic and fragmented, is actually extremely "clear". On its way to the dead, the film keeps losing what is important or not, and at some point acquires its most graceful form, as some of the films of Bresson and Ozu show us. And in many cases, films that look very different at first glance are likely to be located next to each other.

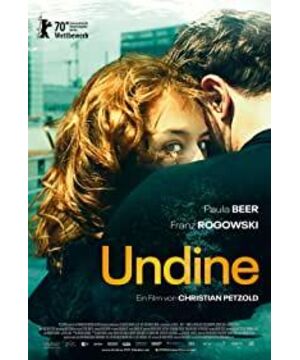

"Wendini"

A recent film that offers a model for exploring the relationship between these two spaces is Petzold's Undine. There is a minimalist paranoia to the opening: Paula Bell is continually drawn back to the specific spatial punctuation of the outdoor seating outside the cafe, first by the gaze, then by the entire body. This is later shown on the map, it is a kind of mark, let a certain part of the space become independent from the original whole, gain the clarity of meaning (in the movie, this is the original location of the inseparable lover) - a A kind of "purging" of film space. At the same time, it is also combined with the desire mechanism of the heroine. Through the process of being constantly "recalled", there are some near-deliberate practices, such as the use of Paula's absence and the reminder of others (almost the usual routine of vulgar melodrama), and the psychological motivation of Paula's gaze is pushed to the map Later, the director used an extra blunt but inexplicably fantastic superimposed painting, which brought lovers and places back to the screen. At the same time, this passage also shows a psychological experience shared by many viewers, that is, "When you go, you feel that the journey is long, but if you go back on the same road, you will obviously feel that time is speeding up." When talking about "Wendini", we often think of "water", "blue sky" and the clear weather in Berlin. These impressions provide perceptual materials for the "clear" space, even including the decoration style and style of the rental house. Paula Bell's eyes.

However, soon, with the departure of the old lover, the film quickly entered another state - "turbid" space. When Paula walked into the cafe, the lover's departure took away the small flag that had been inserted in the space. So, we have to start looking and face possible chaos, like the island in "Adventures". Of course, Petzold didn't let Paula go that far. When she entered the coffee shop and saw an open tap, what did it mean? Maybe it doesn't explain anything, but at this time, when Rogowski accidentally bumped into the cabinet shelf, there were glasses and some stainless steel spoons. The latter fell out of the basket and scattered on the ground. Then the glass fish tank suddenly vibrates (a wonderful metaphor) - going from "clear" to "cloudy" like a whole piece of glass suddenly shatters. And in the bathtub, a simulated ecological environment, there are aquatic plants and divers dolls. All this, except for decoration, is to simulate a "turbid" space to deceive the fish in the tank. This important moment in the film just means a transformation of space.

The "turbid" space provides endogenous power. If "clear" is to build a homogenized kingdom, then "turbid" space contains a variety of foreign substances. The artistic experience it produces is often bizarre, like the ancient legend inserted by Apichatpong in Uncle Boonmee Who Can Retrieve His Past Lives, or the final shot of Boonmi with DV (clearly alien to previous images) When Mi was passing through the cave before his death, it gave the audience the same feeling. The "turbid" space constantly shatters original expectations and creates new ones. It inevitably surprises and confuses the audience, and experiences a sense of rupture in understanding and sensibility. It can be said that one of the pursuits of "turbid" space is to oppose smoothness and use it as a standard to distinguish art and crafts. This seems to be Brecht's so-called "distancing" effect, which opposes the submissive artistic experience and emphasizes the meaning of the so-called "play".

Is that what we experience when Paula kills her old lover in the pool? is this real? Or a dream? How is this possible? And this last question is not a rhetorical question, it expresses our bruised confidence and that we really want to know how this is possible. Another example is the ending, Rogowski seems to choose to abandon his pregnant wife for Paula. is it right? Should this be the case? There are some ethical issues involved, so let's go all the way back to Paula's last phone call with Rogowski. Does this call exist? And when Rogowski walked alone into the blue night for the first time and drowned in the river, we also remembered Paula's attitude before that. And then she also went through some moral choices, such as whether to kill an old lover. It is this chain pattern of repeated backtracking that breaks the linear chain of time. Some people describe this feature as "the temperament of Malamese". Everything that happens underwater needs to be confirmed by watching the video playback immediately, and the appearance of the city can only be explained clearly through the three-dimensional model, replacing reality with form, confirming, understanding, and grasping to obtain certain knowledge. And when the model doll becomes a form of love (a token), the fields of emotion and feeling are eventually replaced by the form of "clear" space. There is a looming fetish inclination here. After the "token of love" is damaged (the inevitable fate of things), it instantly brings indescribable emotions and extreme chaos in the mind of the person involved, and even conveys a certain omen of death in the film. From here we can give a roundabout reminder of Petzold's authorship: modern society is constantly turning up its clarity, but the fragility of this clarity itself recalls greater chaos. Further, we can also point out that his limitation is that he still puts "clear" first on the positive end of value judgments, and imagines "turbidity" as a situation that we should try to avoid (similar to a state of anarchism). ). So, his "Yela" would seem hollow and childish, even though there are many similarities to "Wendini" in it. The "shallow" criticism that "Wendini" may have suffered is instead the film's virtue, liberating itself through a love and a myth. It only takes the fact of presenting a sudden change between "clear" and "turbid" as its most profound purpose. This is also the fundamental reason why Bach's music seems so appropriate in it.

Undine is undoubtedly Petzold's best film. We can probably agree that it is a "clear" movie. This sensibility is also linked to the question of whether the author's style is distinct. Does it mean that a writer with style, or a video stylistic artist, must be "clear"? Style is the hallmark of a film artist. But the definition of "clear" or "turbid" space is not at the author's level, just like Deleuze's proposal of action-image and space-image also transcends the author's theory. Based on what was mentioned above, the transformation of the two spaces is fundamentally abrupt. The different works of an author can naturally be boldly attributed to different spatial classifications. For example, for Bresson, although most of his works belong to that kind of elegant "clear" space, his 1974 work "Warrior Lansinoh" is a veritable "chaos" film. It shows the last glory of a group of people, a style, and an ideology, which must not be broken down, the face is ugly and the cups and plates are messed up. Perhaps it is for this reason that it has been undervalued for a long time. It seems that harmony is the highest standard for a style to be self-fulfilling.

The two spaces are not inherently superior, yet the underestimation of "turbidity" is almost as much as the over-praise for choosing a "clear" space. The latter is represented by most of Haneke's works, and his "angle problem" is first and foremost a problem of calculation. And in Abbas's "As is," we see how what was originally a near-best batch of "clear" films turned into its opposite. It's reduced to some "as-is" copying of the previous author's style, and a conceptual swap at the same time as Biao's acting skills. Again, a good "clear" movie is not the opposite of a "turbid" movie.

View more about Undine reviews